Noah

By Daniel Irvine and Chad Manley

Edited by Tatum Dooley

Noah’s devices began with the elk.

I arrived home and found the station wagon in the driveway: front end crumpled, a streak of blood on what was left of the grille, the dog barking wildly in the yard. Noah was seated at the dining room table. Across from him, an elk had been draped over a couple of sawhorses, its head propped up, leaning against the wall.

I stood for a few minutes, transfixed in the musky, enveloping smell, before Noah spoke. He told me it had stepped into the road, at the curve, by the Williams’ place; He could see its breath in the headlights. Noah would mutter absently in moments of otherwise silent stress—this time something about playing in the forest when he was a kid. I asked him about the car, to which there was no response. We stayed there a while, the three of us—not saying anything. Noah’s eyes were closed; the animal’s dark eyes were open, empty, and the whole room was reflected in them.

Later, I am not sure when, I went upstairs and opened the windows and lay listening to the distant sound of the highway.

In the morning, the animal was gone. But out in the driveway, Noah had screwed together some sawhorses and our coat rack into a four-legged frame, roughly the size and shape of an elk. It was wrapped in reflective tape with two flashing Christmas lights for eyes. He loaded the blinking effigy on the roof of his car and drove it back to where the accident had occurred. He placed it at the side of the road and carefully surrounded it with a circle of stones. He would drive out there, regularly—adding reflectors, changing the batteries in the lights. A makeshift memorial. He never told me what had happened to the real elk; I didn’t ask.

The next device came a year later. We used to hear owls in the neighbourhood—often it sounded like two big ones, and sometimes, the chicks with their seething screeches. We never saw them directly, but at some point we came to find them gone, the trees silent. Noah arrived home early one day, announcing that the sales department had relieved him, just a few months before a full pension. He had an armful of wires and added, blankly, that on his way out of work for the last time he had stripped the CCTV camera system from the company parking garage. He picked up an extension cord, went into the yard and began climbing the taller of our two cedar trees, their bendy limbs threatening to unweight his whole 147 pounds. He tied the infrared camera somewhere up in the branches. Below it, he wired a monitor and ran the cord back up into the tree. I asked him what he was doing, but he replied only that he was putting the owls back. He missed them.

The monitor would remain switched on, where it would sit quietly by the front door, and would broadcast anything seen by the infrared eyeball. Whenever Noah passed by the cedar tree, entering or leaving the house, its red eye would follow him. Out the window, I'd see him briefly pause as he found his own image in the monitor. Noah would often remark what comfort the digital creature gave him. The kids would always stare and tease him about the mechanical owl, but it continued to sit there, up in that tree, at least as long as we paid the electricity bill.

As he constructed his nature devices, Noah seemed to me, if not content, at least purposefully tuned to the diminishing of the world. There was the muskrat wagon, the subscription to the tree allergens—mail-bound cedar, pine, and fir puff balls—and the catapult thing, with the paper moths. There was the Tupperware concert for the frogs, and the gassy one-hundred-foot-long whale balloon with the big eyes. At high tide he'd let it fly right up close to the legislature offices: the roving eye sliding past the windows, scaring the shit right out from under the desk workers. Before coming to visit, the kids began calling me, to cautiously ask what they might expect to find in the house. I don't know if they were concerned for Noah, or for themselves, or if they understood that he was trying to give something back to the world, something he felt that we all had collectively lost. The summer when the rains didn't arrive, he hung an old, blue tarp on movie night—a kind of drive-in theatre—and would broadcast to the neighbourhood his rerun home videos of past downpours. He’d be there, soaking in the show and watching, between fists of popcorn, while the neighbours stayed inside in their own dramas.

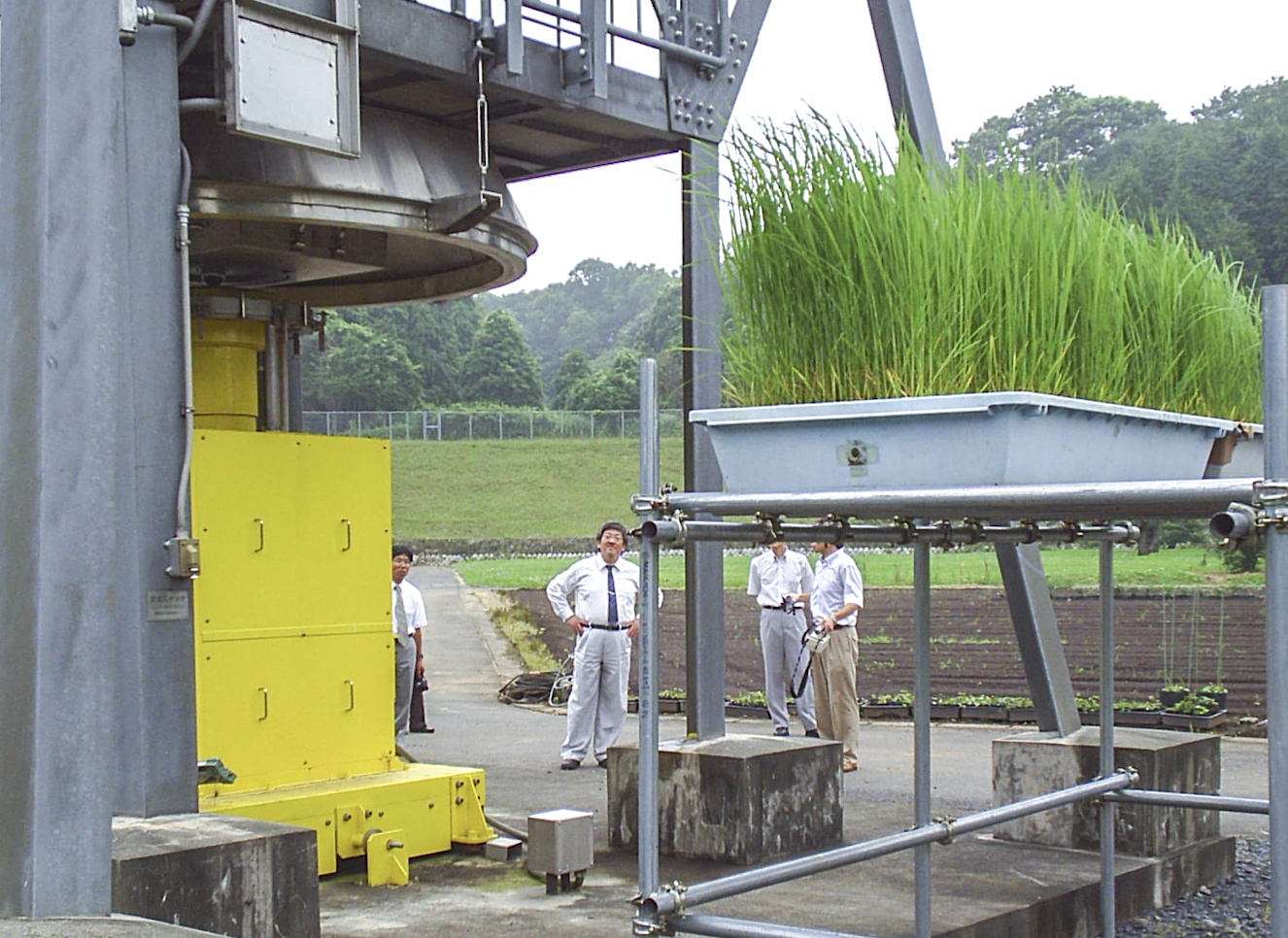

One year, our house suffered a series of earthquakes. Outside the back door, Noah poured a deep, wide footing. Directly atop it, he bolted down one of those gas-powered compactors—one of those vibrating machines used to pack down soil. He wrapped a heavy-duty harness around both the machine and the base of the house. Over the next series of months, the compactor would periodically awake. It shook and rattled the old structure for a few minutes at a time like the cheap, tummy-vibrating belts sold on late-night TV. It wasn't clear how Noah timed out the sequence of tremors, or if he would make any special preparations in the event of the big one. It didn't matter: I soon found myself appreciating, perhaps not the shaking itself, but the surprise it brought and the sense of quickened attention it always left me with. There were arguments initially over the cracked walls and regularly broken dishes. Noah suggested we keep things on the floor from then on. And of course the neighbours complained about the noise and the vibrations we were sending out into the neighbourhood. But our house, our marriage, the world, all felt more alive than it had in a long time.

The creek behind our house had once carried a yearly run of fish from the ocean. Starting about fifteen years ago, the runs returned smaller and smaller each fall, finally and terminally returning nothing a few years ago. When we first moved to the neighbourhood, we’d spend many days down there, counting them, watching them splash as they made their way past our place. When the fall rains pattered on the roof, Noah would sometimes roll over in bed, nudge me, and whisper, “The salmon are here.” After the first year with no sign of the run, Noah began to assemble what he called, “The last last school of fish.” He had laminated cutouts from old Field and Stream magazines—trout, maybe salmon—and stuck them onto a few old transparency projectors. He placed the projectors at the bank of the creek. In front of them he strung a few taut ropes between the nearby trees. Arranged in parallel to one another, each line was offset by a few inches. Like clothes on a clothesline, he hung large plexiglass sheets to each rope, forming a cascading layer of reflecting planes. The sheets were tall—taller than him, taller than me. And wide, maybe five feet across. When the projector was turned on from an extension cord brought from the house, the lens would broadcast a perfect silhouette of each fish. When the breeze blew by, the layers of wobbling plastic would reflect and multiply the fish projection, setting about a wiggling broadcast of his beloved school.

While Noah’s devices were born of the perished and destroyed, they invariably came to take on a life of their own. While I watched him make his way through each construction, I came to focus on the misspent moments of my own life, the opportunities not taken, or what I might do for the not-yet-dead. Noah, however, increasingly found affection for the devices themselves, calling the illuminated fish pet names and tending to their needs obsessively. Perhaps this is human nature, if there is such a thing: to mourn our own inaction with busyness and substitute our own complication for the complex nature that we have lost around us.

Then, one day I found him, dead, collapsed over a crate of lightbulbs. Following his wishes, he was buried in the woods, wrapped in a perforated wool blanket to which he'd sewn on the label: For composting—me and the soil flora.” There was no funeral, but several neighbourhood teenagers helped me with the wheelbarrow, and after little discussion we lowered him down into the crumpled dark. We shoveled him in and marked the spot with some plastic flowers he'd kept by the bed. We said our goodbyes, and I trudged back home for dinner, careful not to disturb the crows that, one-by-one, had begun to roost above him, waiting too, it seemed, for the rains to finally return.

Bio

Chad Manley [IA.AIBC, BCSLA Associate] and Daniel Irvine [Architect, AIBC] are designers working in the related disciplines of architecture, film, landscape and exhibition. Their work explores elements of life, from the city outwards: ephemera and phenomena, myths and material. Together, they investigate relationships between culture and nature, history and future.