Performing Spatial Justice

Transparent Objects

By Cara Michell

Edited by Amrit Phull

Why We Wear Them

A few years ago, I began a clothing experiment to mine a fairly universal concept: how the shapes, colours, symbols and textures that we choose to layer ourselves in can make us feel more—or sometimes less—comfortable. How we dress is directly related to how we feel about our bodies, how we define physical comfort, and how we want to be perceived (versus how we are actually perceived). And it is also directly related to the colour of our skin.

Clothing has long been used as an augmentation of our physical form, giving shape and expression to parts of our identity that wouldn’t otherwise be visible. Clothes can tell us and others what we believe to be true of ourselves, as much as they communicate what we would like others to think of us. Clothing can be both functional and socially expressive, but it can also be the opposite. It can act as a sort of armour: a cloak for the culturally oppressed whose very survival depends on the ability to conceal their true identity and render it invisible to the oppressor.

The 1920s entertainer Josephine Baker, who offers one such example of this duality, used her image to both conceal and dazzle by moulding it into an accepted stereotype of blackness, guaranteeing her safety and acceptance. The American dancer found success performing in Paris, earning praise and attention from the gaze of white audiences in exclusive venues. She crafted an image that seduced an entire city, and eventually the very country she was disgraced from,but even while naked, she was hidden. Her banana skirt, nearly nude erotic performances, and film roles as the “exotic” female subject captivated audiences who happily reduced a powerful, creative visionary to a pretty woman making funny faces on stage. She became not just palatable but adored in her early career by embracing, as her armour, the primitive stereotype that made her audiences more comfortable with her blackness. By stripping down to her bare skin, Baker was in a sense layering on a second skin: one that deflected her audience’s gaze from witnessing her true identity, enough to both entertain them and protect herself. They could, at once, consume the forbidden beauty of her blackness and forget her blackness altogether in the textures of gilded art deco facades and Pablo Picasso’s western interpretations of African “primitivism.” In her book Second Skin, Anne A. Cheng explores the racialized and sexualized body, describing how Baker’s “nude images rely, oxymoronically, on the composition of layered surfaces. Baker’s skin is constantly referring to other surfaces and textures. . . Is “blackness” iridescence or essence?” (1) I would argue that the glimmering “blackness” of Baker’s second skin is exactly the iridescence that covers up her essence.

Playing into an acceptable version of blackness was part and parcel of being both black and a part of the entertainment industry in the early 20th century. The practice of wearing blackface at this time was not limited to white actors. In a New York Times review of Shuffle Along, a 2016 revival of an early 20th century musical originally performed in blackface, John Jeremiah Sullivan writes: “[t]he blacks-in-blackface tradition...emerged from a single crude reality: African-American people were not allowed to perform onstage for much of the 19th century. They could not, that is, appear as themselves. The sight wasn’t tolerated by white audiences”. (2) Sullivan explains how, despite the fact that the elevated position of “the stage had power in it,” white audiences were still willing to watch other white performers on stage in blackface. Within this framework, black performers found a loop-hole. By degrading themselves in the eyes of white audiences and physically layering-on the version of blackness that theatre patrons wanted to see, they were allowed to perform. For the audience, the paint reinforced the subordinate version of blackness they could stomach—one they deemed acceptable and one that was ultimately untrue:

Blacks, too, could exist in the space that was neither-nor. They could hide their blackness behind a darker blackness, a false one, a safe one. They wouldn’t be claiming power. By mocking themselves, their own race, they were giving it up... A strange story, but this is a strange country. (3)

Sullivan illustrates that the power implied by occupying the space of the stage was nullified by blackface. The performers had no choice but to play into a stereotype that gave audiences the type of entertainment they wanted to see: black people degrading themselves. The actors, along with their talent and skill, were no longer a threat. The black paint formed a second skin, at once granting a window into their internal struggle with acquiescing to that kind of degradation, while also obscuring their talent, pride and power. The greasepaint made the actors’ open consent to subordination visible. As if the paint wasn’t just covering up their true skin, but revealing the performance of their suppression. It was the armour that kept them safe. But beneath that layer, their power was concealed and sometimes suffocated. The transparent layer became a cloak, as Darrell Wayne Fields describes in Architecture in Black, because the “conveyance of the Negroes’ identity was, in actuality, its concealment...[blacks] too had to adorn the black face...in order that Whiteness could maintain its distorted concepts of reality under the auspices of progress.” (4) So, while the concept of wearing a transparent cloak may look like a statement of freedom to some, that thick, clear plastic bag pulled over the wearer’s head still suffocates.

These notions of transparency and concealment informed what I called the “Performing Spatial Justice Experiment” in which some friends and I played with this element of “transparency” quite literally. During the roaring twenties, black actors used thick blackface greasepaint as their armour, while Baker earned her safety and acceptance through the use of her glowing nude skin in the Jazz Age. From painted skin to naked skin, what comes next in this quest for transparency and safety in the twenty-first century? I developed a collection of objects that allow us to materialize the things we do to make our white neighbours more comfortable, making apparent the twisted stereotypes of blackness that people submit to. In an environment where my black community is constantly interrogated about where we come from, “what we are,” and why we’re here, the transparency that’s desired from us by white audiences today seems to rest on information. “Where’s your family from?” “Why are you walking in the middle of the street?” “Are you allowed to be playing with that toy gun?” “Who invited you into this neighbourhood?” “How do I know you really intend to buy something?” And if we can’t answer those questions quickly enough, we get dark stares, hushed whispers between friends, discrete calls to security, not so discrete calls to security, hands up in the air, too tight chokeholds. We get shot.

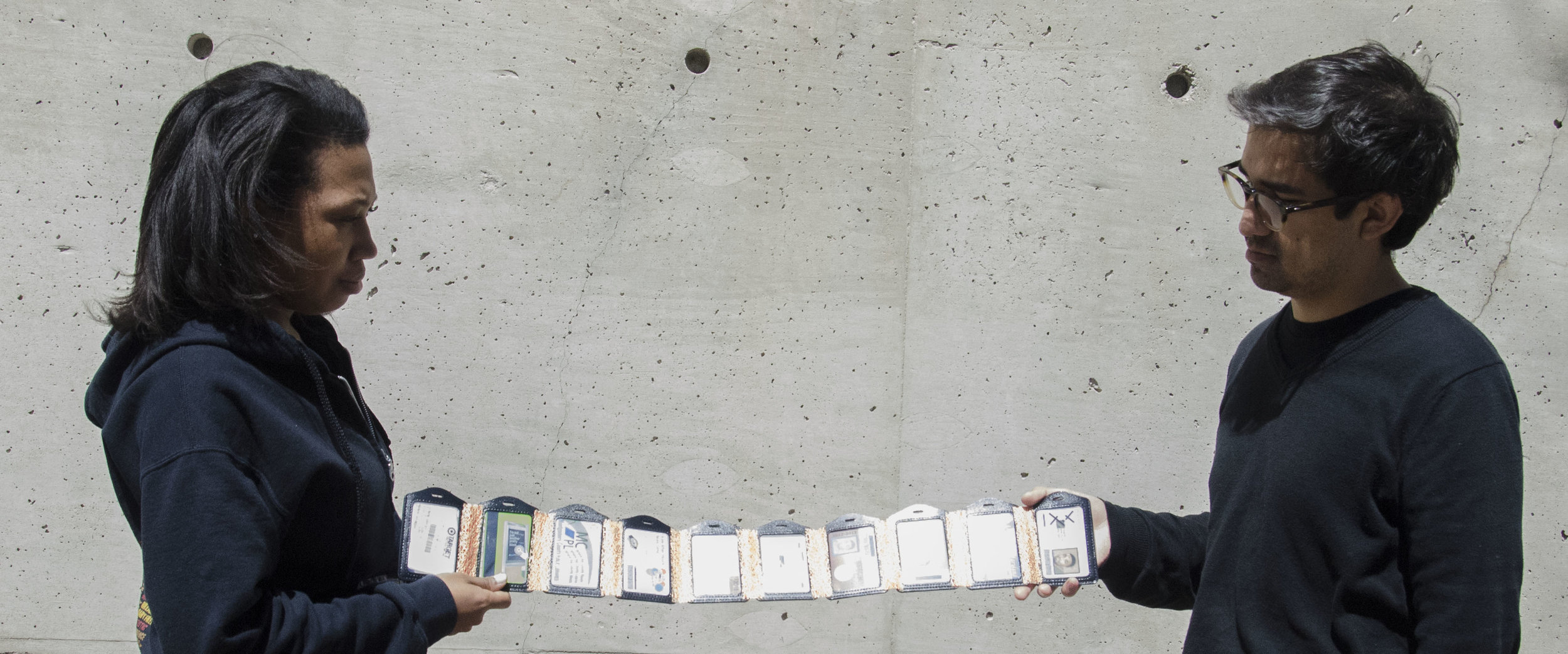

And as we’ve done through the decades, we try to act in ways that won’t get us misread. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. But nonetheless, so many of my friends and family, myself included, seem to be weighed down by this intangible compulsion to submit and to survive. If people are fearful of what’s in our pockets, let’s make them see-through. If they don’t trust us or our institutionally issued life-story, let’s carry wallets that fold out continuously with ID cards and receipts to prove it. If people don’t believe that we own our stuff, let’s tag it with proof (See Image 1). In this awkward moment constructed by America’s coming of age, we are willing to sacrifice the privacy of our bodies, our personal histories and our belongings to keep you comfortable. We are willing to make ourselves so transparent that we have nothing left to hide except our pride. Because when you are comfortable, we are safe.

But these layers of armour weigh cultures down. Playing into a stereotype for one’s own protection is a violation of that person’s truth. It takes energy to be both continually submissive and compliant. The armour is a physical reminder that you don’t belong. So why do we do it?

How We Read Them

My younger brother, Alex, inspired these thoughts in the simple way he manipulated a deck of plywood at his feet. The moment he mounted his skateboard, my brother transformed into a new social creature: no longer some black kid from the suburbs of DC, he was now a skater kid who knew pain, hard work, and a lingo that only he and this community could understand. He seamlessly integrated himself into a crowd from which he might otherwise be segregated, forging new pathways between the spaces where he belonged and where he did not. That $50 Element board nearly earned him a pass from the centuries of racial stereotypes that might otherwise fall on his back—at least in some circles.

But playing into a stereotype for one’s own protection is a violation of that person’s truth. It takes energy to be both continually submissive and compliant. The layers of armour are a physical reminder that you don’t belong.

During a 2017 interview with Art21 Magazine, Jacqueline Gleisner asked performance artist Nick Cave about the origins of his Soundsuits, which he is widely thought to have made in response to the 1992 Rodney King beating and subsequent riots. The Soundsuit’s interior provides a safe cloak for the vulnerabilities that many black and brown people feel, while its exterior projects a non-threatening image for others. In the interview, Cave recalls the initial motivation to engage in these political artworks:

The incident in 1992 put me in a very vulnerable position; [it made me defensive]. I feel like I’m protected only in the privacy of my own space; the moment that I walk out of my home, I can be profiled, and I am looked at very differently. I saw myself differently after [the King beating]. Suddenly, I could be guilty until proven innocent. (2)

By wearing the Soundsuits and transforming their physical appearance, Cave and his participants pre-empt the negative stereotypes that would otherwise be launched at them: “‘I’m making these objects, a secondary skin, and on one hand, it’s about protection, about hiding.” (3) While Baker’s second skin is layers of iridescent distractions, Cave’s are loud colours, shapes, and sounds, “forcing the viewer to look at something without judgment.” (4) In other words, Cave is saying that he cannot travel through public spaces as himself, an artist, a black man, without being judged. But when people are seen only as what their body presents, do they lose the agency to define their own identity, or are they reclaiming it despite social barriers? Both Cave’s Soundsuits and Baker’s performances can be seen as reclaiming agency by distracting audiences with alluring colours, seductive movement, and glittering skin. But both artists straddle the line between subversion and submitting to racism by seeking shelter in a Soundsuit or accepting praise on a stage.

Apart from the scope of art and performance, there are devices we wear for everyday living. Some are layered with even more politicization, whether gendered, racialized, or xenophobic, depending on the geographic context. In her book Veil, the human rights activist and attorney Rafia Zakaria states how in order “to survive that last year of school, I needed a visible act of contrition—and so I chose the headscarf.” (5) I’m interested in the phenomenon of social misreading, of subscribing to the "non-threatening" caricature or submitting to being misread. As I see it, a misreading occurs when someone assesses another person’s character based solely upon their appearance and the known stereotypes that it invokes. The devices we deploy to combat that misreading must also change between one space and another. The backdrop of a convenience store or mall boutique warrants some transparent pockets, sewn over the place where most people tuck personal items into sweatshirts and pants. The backdrop of a stopped car, front door, or university library requires an ID wallet with a million folds, holding one identity record after another. Because when your presence is already unwanted, a plastic window to reveal the government issued proof of your right to be there is more valuable than a leather slot for your $20. The stereotypes deployed in a misreading are almost always chosen according to the physical space that serves as a backdrop.

Jason Goolsby, a black teenager in DC, was tackled by police three years ago after deliberating whether or not to withdraw money from his local ATM. The police assaulted him because they received a fraudulent 911 call from a woman who misread his presence at the ATM after Goolsby opened the door for her. (11) She assumed that Goolsby’s motion to open a door signified a black boy’s intention to rob her. Not common courtesy. Thus, that street corner not only became a space of misreading, but also a space of injustice for Goolsby. The space of injustice materializes when the space of misreading is played out with tragic consequences. It occurs when people of colour are wrongly criminalized, then victimized in a site where the physical presence of their body is met with racialized assumptions.

My brother was able to deflect some of those misreadings with his skateboard, but as soon as he entered a space where people did not recognize the skater persona, his armour disappeared:

I know in convenience stores I just… I feel like there’s a lot of people… I just try not to put my hands in my pockets… ‘cause people are gonna think that you’re trying to pocket things. And I always feel, like, successful when I go up to the counter and then pay…because then they know that I’m not stealing anything. (12)

And he anticipates a different type of misreading when walking home at night:

… and then I feel like someone may think of me as a threat, I’ll just be friendly and say hello so that they can, one, feel bad for having judged me, and two, feel more comfortable. Probably been doing that since middle school. I don’t think anything triggered that. It’s just that I walked around at night a lot. And I’m a black guy, usually wearing a hoodie. So, I don’t know... sometimes people would put their heads down immediately and you know, walk a little faster. (13)

So while my brother was able to deflect some of these misreadings with his skateboard, I hope for a future in which he doesn’t have to.

In this pervasive culture of misreading, a person coloured brown is considered something less than human, less than sacred, and nothing more than a threat to the white bodies, which are considered both human and sacred. This is not an urban problem. This is not a Southern problem. This is not a police problem. It is a spatial problem. It is an American problem, and it has run through the colony’s veins since its inception.

This American problem plays out as a distortion of the black body and mind. Knowing that you are probably seen as a different kind of threat in a different kind of space (but nonetheless a threat in almost every space beyond your home—and sometimes there too) makes you change the way you move through those spaces. The anticipation of racism is burdensome. It affects the way you think, the way you talk and the way you hold your body: “I am afraid of walking into stores without knowing exactly what I want to buy and that it is in stock. Because people might think that if I walk out without first hitting up the cash register, I must be stealing something,” says Alex. (14)

Wielding a skateboard as visual armour, cloaking oneself in a Soundsuit, or playing into a caricature all seem like ways of totally obscuring the self. But I also read these decisions as a vulnerable act of revealing oneself. These habitual acts of projecting only what others want to see (or what they are comfortable seeing) are so deeply embedded in our minds and bodies that by the time we reach adulthood, they are part of us. This habit of cloaking ourselves is just as much an act of transparency as it is an act of obscuring the parts of ourselves that others misinterpret as a threat. It is a violent act of digging up the embodiment of our greatest insecurities and wearing it on our skin. What made James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son so effective is his illustration of the choice between performing the violent spectacle of transparency on yourself or submitting to the violence of misreading. It is a lesson that I learned in grade-school: a perpetual balancing act between selfhood and the identity we must project to stay safe.

But why should they carry this burden alone? When I first started studying sculpture as an undergraduate student, I experienced a powerful catharsis in the act of externalizing my thoughts as physical objects—making sculptures. So, could the same healing power apply to the burden of wearing that layer of transparency? And could that, in some way, help to restore some of the agency lost?

When We Internalize Them

Whenever Alex and his friends grind across a new rail or bench, their boards leave a mark: a colourful blur of paint transferred to the concrete, an imprint of raw motion frozen in time. That act becomes a shared visual experience that remains long after Alex’s crew is gone. When my brother walks out of a convenience store, hands hovering over pockets until the moment when he can finally reinsert them, that experience of degradation is cumulatively imprinted on him, ingrained in his muscle memory. He uses that body language, hands hovering over pockets but never entering them, as a transparency device—rendering his submission explicitly visible to those who might fear him. He makes his intentions just as transparent as if he shouted out “Hey! I came here to shop. I have no intention of stealing anything. I’ll leave you undisturbed in just a minute.”

In the introduction to Souls of Black Folk published at the turn of the 20th century, W.E.B. Du Bois describes the burden and double-edged sword of wearing these transparency devices and being the only ones to internalize them. He depicts a movement towards freedom of body and identity, one that we still pursue today with the acknowledgement that that freedom, that authenticity of self, comes at the price of misreading and violence. Du Bois narrates the awakening of the newly freed African American, writing, “...[he] began to have a dim feeling that, to attain his place in the world, he must be himself, and not another. For the first time he sought to analyze the burden he bore upon his back, that dead-weight of social degradation partially masked behind a half-named Negro problem.” (15)

Without being our full, true selves, we fail to attain our place in the world. We are left in limbo, carefully navigating hostile landscapes that remind us, time and time again, that they don’t want us unless we are wearing masks. It’s a conundrum. We cannot find our place without being ourselves, but we are violated by misreading when we act as ourselves—when we refuse to contort our bodies and minds to fit within a simplified description of what a Black person is and what we can do in certain spaces. “The Nation has not yet found peace from its sins; the freed-man has not yet found in freedom his promised land...” (16)

In making the Performing Spatial Justice project, I wondered if there were a way to make this burden of transparency visible to everyone and not just the people who bear their wounds.

A few years ago, I decided to just start asking my family and friends about their experiences with misreading and transparency. In many of these conversations, people said that they were not fully cognizant of the various ways that they contorted their bodies, adjusted their clothing or rerouted their paths in order to avoid being misread. But once given enough time to mull over the idea, my friends and family became increasingly aware of the countless variations of this transparent layer that don when moving from one space to another. It is so deeply rooted that they often don’t even see it themselves.

Because of the fear that our word is not enough prove our identity and that our appearance might invite undue scrutiny, we never leave the house without at least a few forms of ID. Because the act of reaching into our pockets to find that ID might invite violence, we keep it readily available and transparently visible. Three stories in particular stood out during my conversations with friends and family.

My brother spoke about an experience a few years ago when his car, parked in front of a friend’s house, was broken into overnight. He called the police that morning, and they came to investigate his report in Takoma Park on the historically whiter, Maryland side of the border with DC. They first asked for proof of license and registration, then for proof of identity, proof he actually owned the car, proof that it was his stuff that got stolen, then for an explanation of what he was doing in that neighbourhood. By the time they got through interrogating him about why he had a car, and why he had friends, and why he had friends who lived in a white neighbourhood, and why they let him stay there overnight, no one had much energy to investigate the original claim of theft. So he left without his stuff, and with a fear that if he ever left the without a paper to corroborate the truth every element of his life, his black ass would be shit-out-of-luck.

When speaking to Milan, her stories were reminiscent of a recurring element in those of my brother's. She described the deep-seated fear of walking into a store keeping hands out of pockets, since touching your pockets means you are pocketing something. And when you’re already being followed around by not-so-discreet store employees, being mistaken for a shoplifter is not a mistake you want to make.

Talking to Alex’s buddy Kalanzi made it clear how precarious black ownership can be. After all, we were brought here to be bought and sold, not to acquire assets of our own. Back when the boys were in high school, Kalanzi was skating down the street from our house. In his own words:

I was going really fast and I fell. It was really bad, like I flew forward, and my knee was bleeding, and my hand was scraped…all my belongings were everywhere. And I took, like, five minutes just in the middle of the street to collect myself. I went over and picked up my skateboard and my phone. I looked at my phone for a long time and I thought that it was broken…and the house that I happened to be in front of…this really old lady came out of her house. She was very hostile towards me. She was like, “What are you up to? What did you just pick up?” And I said, “I’m sorry if I startled you, I just fell.” And you could see that I was really bruised up and I was bleeding. And she said “I just saw you pick something up that I don’t think belongs to you.” I was like, “Oh, this is just my phone. I don’t know what to tell you.” And she was just really angry at me for picking up my phone that she didn’t think belonged to me… (17)

So many people in this country are marginalized in such frightening ways. So I feel like I should pay respect to that somewhere in the piece. I drew from stories shared by family and friends that reflect the false transparencies we wear in order to navigate a multitude of spaces safely and freely. In our everyday use of these “cloaks” only the result is visible: the docile, friendly, sassy, hard-working, minstreley, “oh no you di-n’t” diva, coolcalmandcollected with swagger, radio-voiced, respectability politicked caricature of ourselves. But all those painful bits that we stitch together to make that transparent cloak—the layers of internalized inferiority and knowledge that our presence is not wanted—remain invisible and unacknowledged within us. In fabricating these objects, however, I hope to make this violent process visible too. Implicating everyone.

For my brother’s police encounter, a transparent identifier is provided by the ID Foldout. If this was mass market, the ad would probably sound like: “sick of shuffling through your glove compartment looking for license and registration when the police stop your car? Tired of frantically searching for mail or proof of address when the neighbours accuse you of breaking into your own home? Have everything ready like a quick sleight of hand with the ID foldout.” Who needs a wallet when you can have ten forms of ID, receipts and the envelope from your utility bill at the tips of your fingers? With this device, I removed the all other parts of the wallet, leaving only the transparent ID pocket. Like an accordion fold-out, this object allows you to simultaneously display the many versions of you that make white people more comfortable.

In her Object Lesson book, Driver’s License, Meredith Castile describes the many identity markers that come to mind when a fellow German train passenger lays eyes on a US driver’s license: “renegade individualism” “rule-breakers” who “value dissent”, “who invent”, who “follow gut feelings” (18). But this leaves out the very different associations that are made when a black or brown face is visible on that same ID. It becomes a card for defence, not just one for liberation and passage into certain privileged spaces. It's met by suspicious looks up and down from the photo to your face when cashiers try to verify if that credit card really belongs to you. It's met with requests for a convincing narrative to match your address (Alex's story) or a request for student ID to prove that you're on campus for good reasons. In fact, last May, a number of US news outlets reported that a black graduate student had been confronted by campus police because she was napping in a dormitory common room. The frustrated student responded, saying “I’m not going to try to justify my existence here.” Despite the fact that she was surrounded with her books and papers, police insisted that she prove she belonged there. But showing her student ID and keys was not enough, as the police officers held her until they could verify her enrolment with the University registry (19).

For Milan’s convenience store runs, a transparent body is provided by the Compliant Pockets. If the opacity of our clothing is making people uncomfortable, making them wonder if we slipped a candy bar behind the fabric, let’s just make them transparent. Forgo any sense of privacy and rip apart your clothes at the seams to replace what you lost with a thick sheet of plastic, stitched vigilantly back on to the site of that trauma. Why not put all our belongings on display — keys, tampons, cell phone, loose change and pocket lint — so no one has to wonder? And if no one has to wonder, we don’t have to endure the wary eyes trailing us.

When dissecting a 19th century wanted ad for Ralph, a fugitive enslaved man, Assistant Professor Clare Mulvaney posits that the advertisement’s reference to Ralph’s pockets “suggests that freedom means being able to carry one’s possessions.” (20) So is accusing someone of not being the rightful owner of their possessions akin to questioning their claim to freedom? Mullaney hypothesizes that “[p]ockets help determine who gets power and who is deprived of it[,]” tracing the radicalized and gendered history of removing pockets from women’s garments and criminalizing black people for using them. (21) So, what does it say when you allow the contents of your pockets to be visible? Is it submitting to the position of not being free enough to have pockets? Or is it a subversion of the expectation that you're hiding something, as if to say ‘I'm free, I'm proud and I'm not going to hide it?’ Do the pockets give you breathing room to be honest about who you are and what you’re carrying, or does their thick plastic suffocate you?

“To trace who has pockets and who is denied them makes us consider to what extent being a subject means having things, and being able to access them.” (22)

The transparent object series takes that one step further, asking how a person's subjectivity is further complicated by the declaration that you have and can access things, and aren't afraid to let the world know what they are. With freedom comes the ability to walk openly and freely in the world without having to hide yourself or the things attached to you. Which is why, for Kalanzi’s skateboard wipeouts, transparent belongings are provided by the ‘Proof-of-Purchase’ stickers. Apparently, it’s not enough just to let people see what you have. You must also prove that those things are yours. The ‘Proof-of-Purchase’ concept imagines stickers, printed with registration numbers for every object you buy. (See Image 6). That number, in turn, can connect anyone confronting you to an online registry stating your ownership of the object in question. Is that what my neighbour was looking for on the back of Kalanzi’s iPhone?

I sometimes need to remind many people of the fact that these objects are rhetorical devices, not a bandage for our pervasive racist problems. The issues of misreading and spatial injustice discussed here are absurd, and we need an equally absurd language (whether visual, tactile or verbal) to attack them. To illuminate the injustices my friends and I experience in this way, by making clothes and accessories out of other people’s trauma is difficult and ethically tricky. To grow up in an environment where you are not wanted is difficult and psychologically tricky. To understand as a young child that your body, your beauty, and your thoughts are often undervalued by your teachers, your peers, and your country’s majority is difficult and painful. We live in an environment where an extraordinary amount of value is placed on visual narratives and where our identities are read through DMV headshots, the brands printed on our shoes, Instagram posts, and personal websites. So, is this visual arena not one of the most effective places to make an argument about who is and isn’t allowed to be themselves or maintain some semblance of privacy?

The ID Foldout, Transparent Pockets, and Proof of Purchase stickers all tell a story that is so deeply embedded with the shame and fear that come with searching for acceptance and safety in a place that refuses to give it to you. That story gets buried so deep in the unconscious habits of their wearers that it would otherwise be invisible to everyone else. Making these objects and wearing them around unveils an opportunity to let other people see and understand in a universal language that is both visual and tactile. When I wear these things as a performance, I am first performing and anticipating injustice. But by calling out the absurdity of the injustice with the equally absurd devices I am wearing, I am also referencing a future where my pockets, wallet, and stickers are no longer necessary.

Editors’ Note: An excerpted version of this essay was published in the print edition of v.40 Devices under the title “Why We Wear Them”

Endnotes

(1) Anne Cheng, Second Skin: Josephine Baker and the Modern Surface, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 110.

(2) John Jeremiah Sullivan, “‘Shuffle Along’ and the Lost History of Black Performance in America,” The New York Times Magazine, March 24, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/27/magazine/shuffle-along-and-the-painful-history-of-black-performance-in-america.html

(3) Ibid.

(4) Darell Wayne Fields, Architecture in Black: Theory, Space and Appearance, (New York: Bloomsbury, 2000), 23.

(5) Cameron Kunzelman, “Black T-Shirts: The Original Invisibility Cloaks,” The Atlantic, September 13, 2013. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/09/black-t-shirts-the-original-invisibility-cloaks/279655/.

(6) Nick Cave, “‘Is there racism in heaven?’ An interview with Nick Cave”, interview by Jacquelyn Gleisner, Momentum, Art 21 Magazine, January 17, 2017. http://magazine.art21.org/2017/01/17/is-there-racism-in-heaven-an-interview-with-nick-cave/#.XDDh7c9KjBI.

(7) Nick Cave quoted in “The Visual and the Musical: Nick Cave’s Soundsuits Invade Metro Detroit,” interview by Hillary Brody, IXITI, June 16, 2016. Retrieved from www.cranbrookart.edu/museum/nickcave/the-visual-and-the-musical-nick-caves-soundsuits-invade-metro-detroit-ixiti-com/.

(8) Ibid.

(9) Rafia Zakaria, Veil (Object Lessons), (New York: Bloomsbury, 2017), 16.

(10) William M. Morgan, “Race Men (review),” American Literature. Vol. 71, No. 4, December 1999. Duke University Press. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/1447

(11) Hermann, Peter and Victoria St. Martin, “ Detention of black teens by police outside D.C. bank sparks protests,” Washington Post, October 14, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/public-safety/detention-of-black-teens-by-police-outside-dc-bank-sparks-protests/2015/10/13/055203d6-71c1-11e5-9cbb-790369643cf9_story.html.

(12) Alex Michell, Interviewed by Cara Michell. March 12, 2016.

(13) Ibid.

(14) Ibid.

(15) W.E.B. Du Bois, “The Souls of Black Folk, (New York: Taylor and Francis, [1903] 2015), 4, Kindle.

(16) Ibid, 4.

(17) Kalanzi, Interviewed by Cara Michell. March 2, 2016.

(18) Meredith Castile, Driver’s License (Object Lesson), (New York: Bloomsbury, 2015), 4.

(19) Cleve R. Wootson Jr, “A black Yale student fell asleep in her dorm’s common room. A white student called police.” May 11, 2018. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/grade-point/wp/2018/05/10/a-black-yale-student-fell-asleep-in-her-dorms-common-room-a-white-student-called-police/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.ebc7020d96be

(20) Clare Mullaney, “The Social Advantage of Pockets,” The Atlantic. December 21, 2016. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2016/12/pockets-object-lesson/511385/

(21) Ibid.

(22) Ibid.

Bio

Cara is an urban planner and artist, currently based in New York City, where she practices planning at WXY Studio. She holds a Master in Urban Planning from the Harvard’s Graduate School of Design and a Bachelor of Arts in Art and Archaeology (Program in Visual Arts: Sculpture) from Princeton University. In 2015, Cara became a Co-Chair for the first biennial Black in Design Conference, hosted at Harvard University.