Volume 40.2 Collect

Text by Miriam Ho and Aisling O’Carroll

Collecting is an essential first step to the process of knowledge creation. In the scientific method, a science experiment’s success relies most of all on the empirical data collected through observation. The material that is collected can be quantitative or qualitative, but it is only from this array of new information—selectively gathered and recorded—that patterns and knowledge emerge. In processes of collecting, the emphasis and value is most often focused on the collected material itself, be it images, artifacts, or measurements: these materials inform new understandings; their patterns reveal new conclusions.

Just as revealing as the material gathered, however, are the tools for collection. These devices, as vessels to contain physical or intangible matter, or instruments to record sensory and numerical data, can govern, inform, or transform what is collected. The two archival images presented here—the Stasi camera and the Wardian case—speak to the significance of how we collect, whether it is by means of stealth to gather information for means of monitoring, detection, or control, or pragmatic engineering to ensure the safety of the specimens collected. Inseparable from the act of collecting are the processes of recording, interpreting, classifying, cataloguing, indexing, and/or archiving the collected material and information. Nowadays much of what we collect is virtual, and yet these devices still resonate: we can see their contemporary counterparts in the digital data collected (with or without our consent) as well as in the physical infrastructure of collection that proliferates (somewhat more conspicuously) in our public spaces today. Furthermore, the practice of material collection in research and scientific study continues to face the same challenges of time and distance, which are met with more elaborate modes of collection and preservation, such as the mobile freezer containers used to transport ice cores and the extensive refrigerated libraries that house these frozen collections around the world. The human instinct to collect in order to obtain, preserve, and perpetuate knowledge persists even as technologies evolve.

Image 1 | Specially crafted Wardian cases were used to send plant samples from the Buitenzorg Botanical Gardens, West-Java, back to the Netherlands, 1913. Courtesy of the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, TM-10010760

In the nineteenth century, as botanical sciences developed and research expeditions broadened, the challenge of safely transporting live specimens over long distances (and rough voyages) was met with intense experimentation into the design of cases to carry such specimens and plants. Improving on earlier attempts to develop an appropriate case with wood and glass, the London physician Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward introduced “an airtight system in which transpiration inside the case to provides sufficient moisture to keep plants alive for extended periods.” [1] Following the first successful transport of plants to and from Australia 1833 and 1834, the eponymously named Wardian cases were widely used in the circulation of plants between all parts of the world.

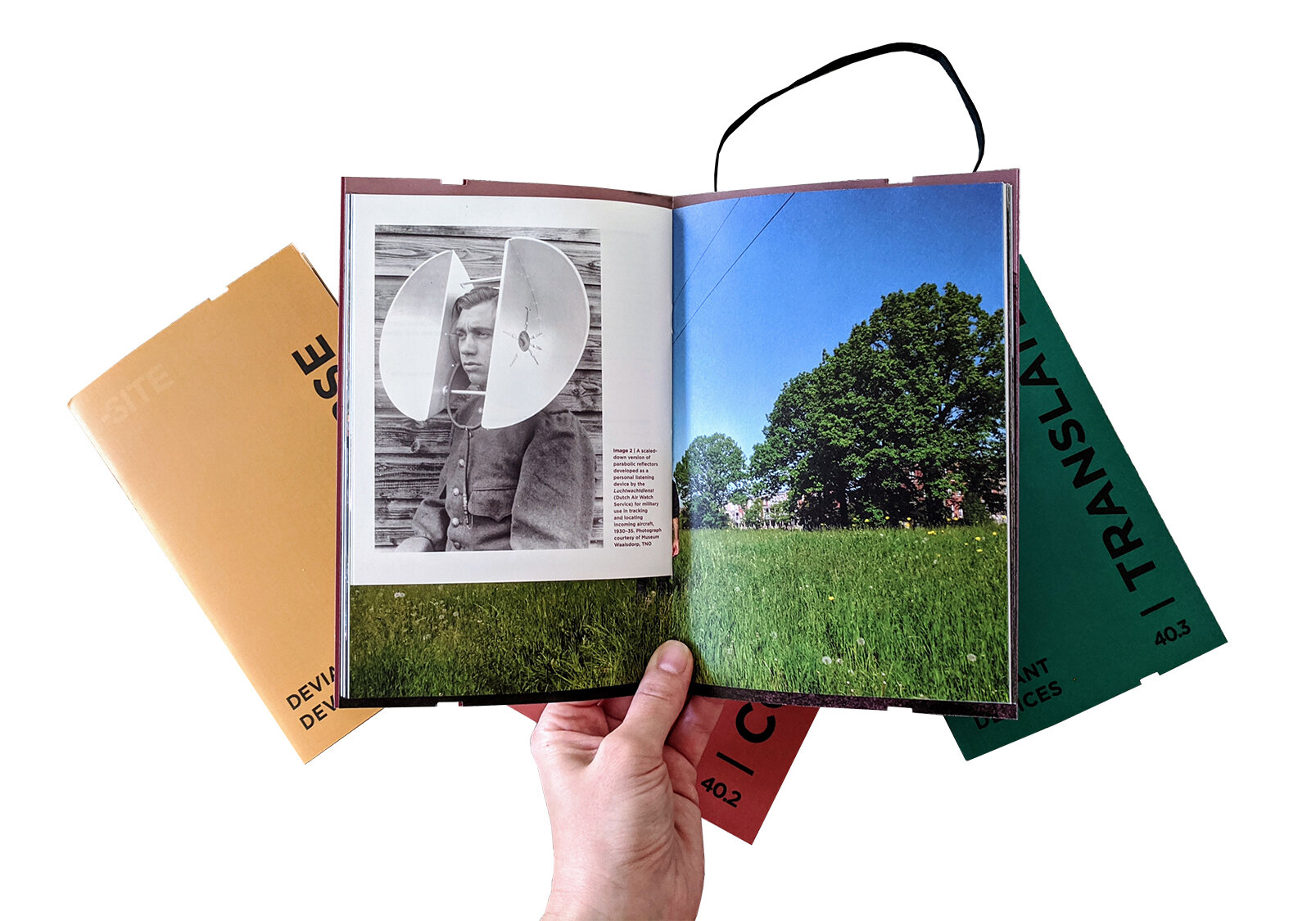

Image 2 | Camera modified to disguise in a buttonhole for surveillance use by the Stasi in the German Democratic Republic. Courtesy of the Stasimuseum Berlin, photograph by John Steer

The Stasi, or Ministerium für Staatsicherheit (Ministry for State Security), was the secret police agency of the Germany Democratic Republic from 1950 to 1990. The agency was responsible for both domestic political surveillance and foreign espionage. Their widespread effort of spying on the East German population was coordinated through a network of officers and citizen-informants. The latter’s main tool for collecting and providing information was the camera. Secret cameras were fitted into purses, wallets, ties, watering cans, birdhouses, and endless other personal and public objects to maintain close and continuous surveillance of the population.

Notes

1/ Luke Keogh, “The Wardian Case: How a Simple Box Moved the Plant Kingdom,” Arnoldia 74, no. 4 (May 2017): 2–13.

In this pamphlet:

Productive Devices a conversation with Mark Smout, Laura Allen, & Geoff Manaugh

Archive of Affinities by Andew Kovacs

Coded Colours by Elaine Ayers

Small Adjustments by Sandra Smirle