Volume 40.1 Perceive

Text by Ruth Jones and Aisling O’Carroll

The French phenomenologist Maurice Merlau-Ponty called sensing a “living communication with the world.” He conceived of sensorial perception as a bodily experience of ambiguity and uncertainty that leads to truth through indeterminate, though immediate, means. However, he argued that this experience becomes more removed as we invent ways to objectively measure perceived phenomena with any scientific precision. We think of perceptual devices as extending our senses and expanding our worlds—things that let us listen in on lightning storms thousands of kilometres away, that detect incursions into spaces we’ve claimed, keep watch when we’re absent, or that pull a three-dimensional ship from a flat wall as we pass by. We think of them, in short, as determinate, as offering information that we can use.

But perceptual devices have no obligation to make the world known with any kind of precision. A soldier listening for enemy aircraft or a painter gazing into a filtered landscape can turn the inputs their devices offer them into information and action. Or they can listen longer, gaze more deeply.

A perception device might start to oscillate, at one moment seeming like a window into an unknown world (bird calls in the midst of airplane engines, a solar storm meeting the earth) and the next revealing its limits, capturing only what passes through a limited perceptual field, leaving doubts about what observed patterns mean (a single plane or four, flying in formation?). A device intended to refine a view might, in a different light, hold shadows and mysteries. The anamorphic image distorts as you move past it, the viewing tool becomes a scrying mirror. Our perception of the world shapes the way we inhabit it, whether our devices sharpen the information they absorb or open to something more undecided, unformed, and mysterious through degrees of filtration, distortion, and interpretation.

Image 1 | Claude Lorrain mirror in shark skin case, believed at one time to be John Dee’s scrying mirror. Front three-quarter view. Case open. Graduated grey background. Science Museum, London, CC BY

The Claude mirror is an optical instrument that was in fashion among painters, poets, and picturesque tourists in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The slightly convex, darkly tinted mirror had the effect of framing a view while simplifying its colour and tonal range to achieve a pleasing painterly quality reminiscent of the popular landscapes of seventeenth-century French painter Claude Lorrain. The dark lenses reduced the brilliancy of natural light to a range that could be captured by paint pigments. Different tains created various aesthetic effects, much like the filters on a smartphone—a black foil to modulate bright sunshine or a silver foil to enhance cloudy days. These dark mirrors were also, less commonly, used in occult practices—their distorted reflections seen by practitioners of black magic to be a portal or device for summoning and viewing spirits from another world. [1]

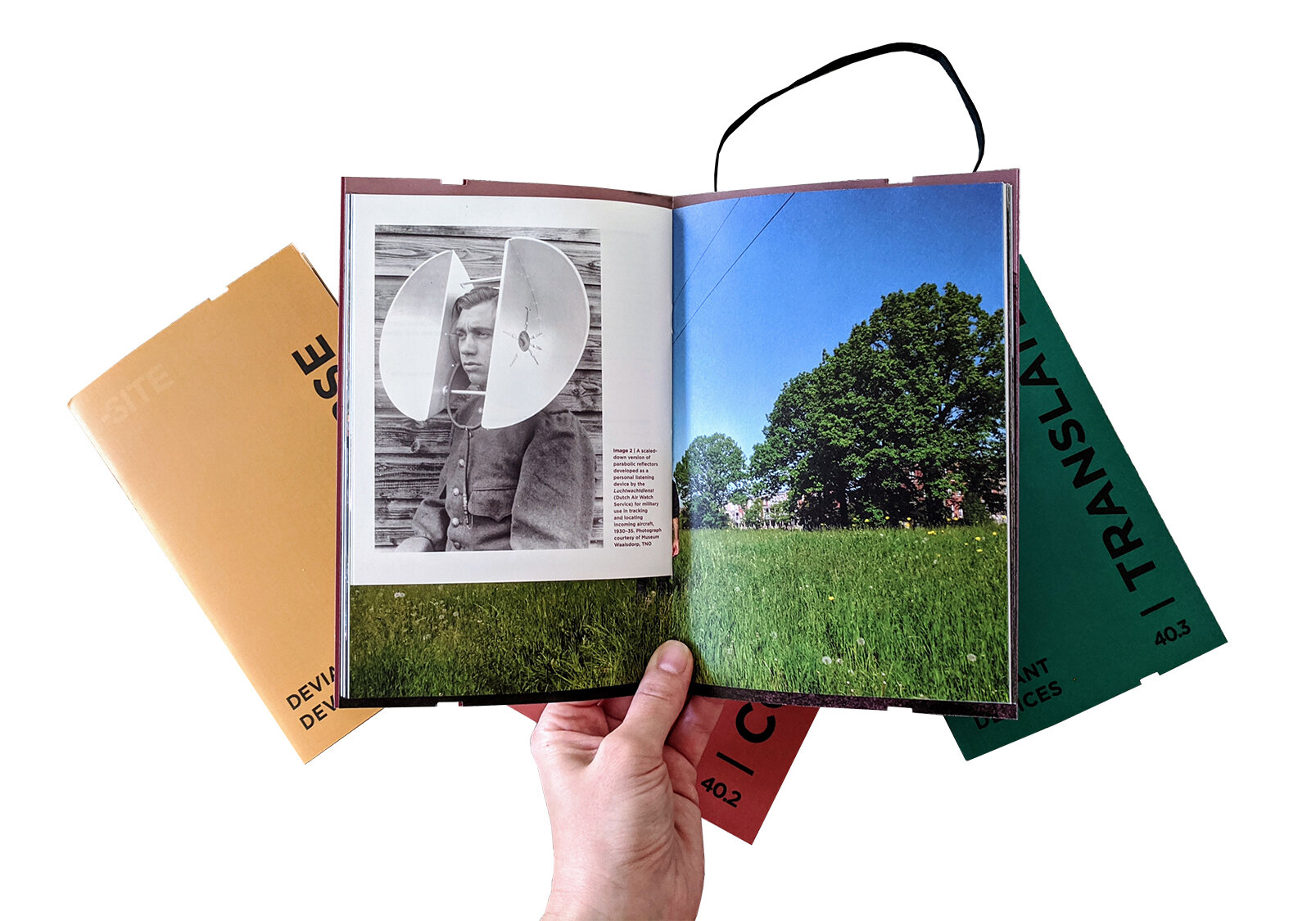

As aircraft became increasingly prevalent in warfare following World War I, the need to detect and locate planes at a distance became crucial to defending against aerial attacks. Early detection devices typically relied on sound: in the Netherlands, the Luchtwachtdienst (Air Watch Service) managed a permanently operating early-warning system composed of official, manned detection towers and voluntary listeners to identify and report enemy aircraft. Based on the parabolic sound reflectors used in towers and buildings to locate aircraft, a scaled-down version was tested as a personal listening device, to enhance one’s auditory perception. [2]

Image 2 | A scaled-down version of parabolic reflectors developed as a personal listening device by the Luchtwachtdienst (Dutch Air Watch Service) for military use in tracking and locating incoming aircraft, 1930–35. Photograph courtesy of Museum Waalsdorp, TNO

In this pamphlet:

The Centre Cannot Hold by Charles Stankievech

The Blindspot by Eric Cadzyn

The Distance of the Tactile by Thi Phuong-Trâm Nguyen

How to Listen to the Sky by Dan Trapper

Notes:

[1] Arnaud Maillet, The Claude Glass: Use and Meaning of the Black Mirror in Western Art (New York: Zone Books, 2009).

[2]“Air acoustics: small, personal listening devices (1930–1953),” Museum Waalsdorp, accessed November 1, 2019, https://www.museumwaalsdorp.nl/en/airacous/early-listening-devices/.