Scripting the Neoliberal City

By Danika Cooper and Zannah Mae Matson

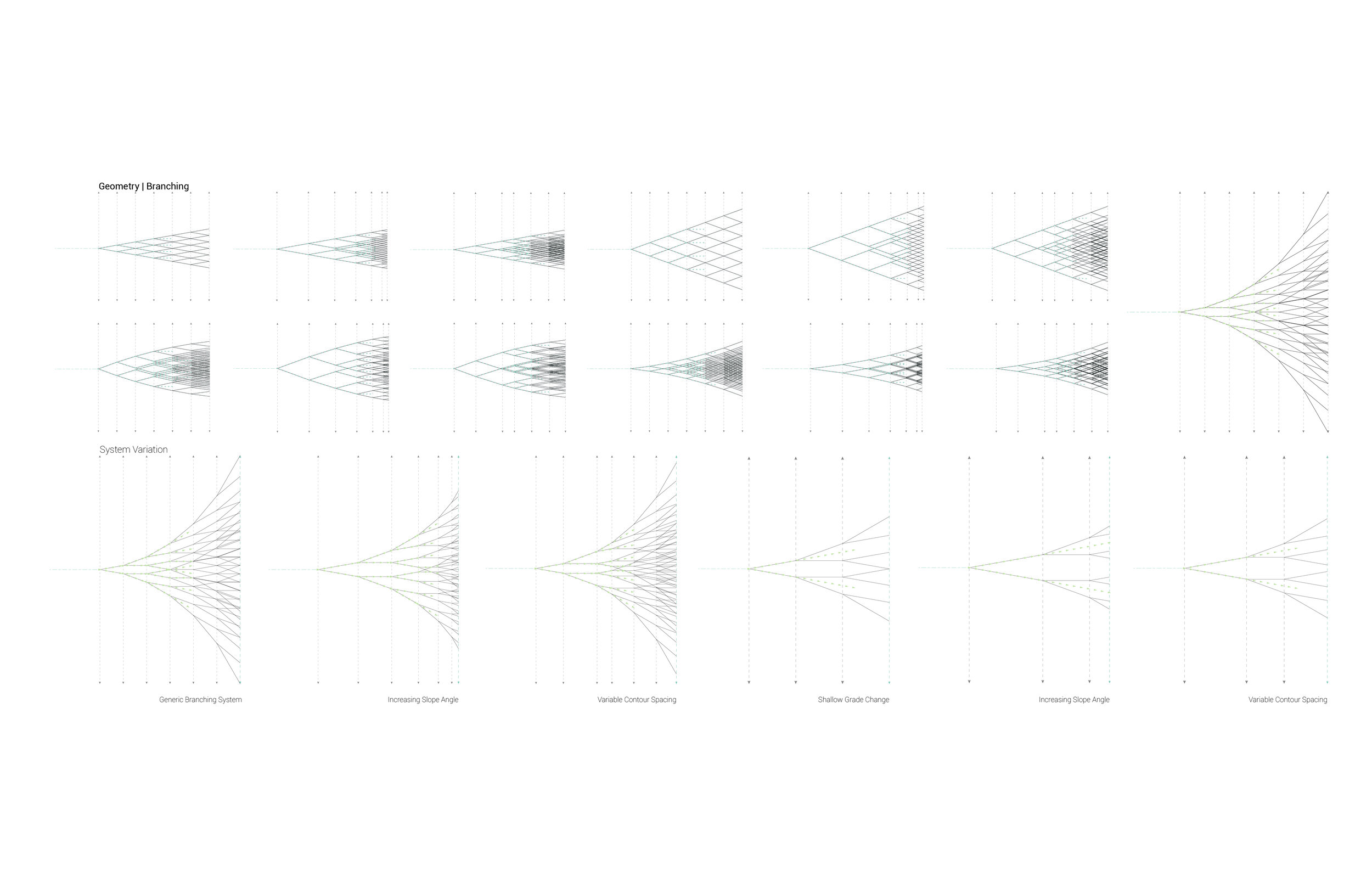

In 2006 Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA) won an international architecture competition to reimagine the industrial district of Kartal-Pendik as a bustling new hub of Istanbul. ZHA imagined the district as a collection of fluid architectural and landscape forms woven together to offer a central business district, high-end residential development, institutional buildings, and tourist and cultural attractions. According to the ZHA website, the design was “articulated by an adaptable urban script that generates different typologies of buildings in response to the different demands of each new district; creating a porous, interconnected network of spaces throughout the city.” (1) The Kartal-Pendik project has become an icon of this script-derived urban design, in which values are codified as design commands and digitally executed to produce architectural forms. Within the discourse of post-industrial revitalization, the Kartal-Pendik project represents a prevalent approach to contemporary urban agendas: one that emphasizes data-driven, aesthetic methods while often reproducing and exaggerating the political and social unevenness of the neoliberal city.

Kartal-Pendik, located southeast of central Istanbul, experienced rapid urbanization in the mid-twentieth century as migrants from Anatolia were drawn to the city’s burgeoning textile industry. With the liberalization and increasing globalization of Turkey’s economy in the 1980s, the district was de-industrialized, such that large swathes of land were abandoned and, in turn, adjacent residential neighborhoods were disregarded. Federal redevelopment efforts began in the early 2000s with the ambition to the modernize Turkey and establish Istanbul as a world city. (2) In order to assert its prominence globally, Istanbul’s municipal government held an architecture competition in the hopes of attracting international attention and generating development proposals for the Kartal-Pendik district.

ZHA’s winning scheme relied heavily on digital, parametric models to create and represent the design. Derived from a scripted approach to urban form, input parameters were modified and adjusted to respond to specific local conditions, however, the nuance of this responsive model failed to incorporate the social and political context of the site. We emphasize the ZHA proposal because it reveals a political and economic outlook for the city through its representational choices and scripted hierarchies: the design visually connects a new, high-end development with multi-modal transportation corridors, emphasizing the relationship between these urban elements using images of a sleek, hyper-stylized digital model. At the same time, the model makes it appear as if the regenerated zones have almost no connection—spatially, visually, or socially—to the surrounding neighbourhoods and their residents. The model does the dirty work, so to speak, through its use of colour and scale, to implicitly demonstrate that the urban form will bar the surrounding neighbourhoods from the benefits of Istanbul’s new metropolitan centre.

Innovations in programming scripts since the 1980s underline the indispensable role of the digital model within architecture as both a space for experimentation and a means of representation, making it a fundamental tool in contexts where the scale and complexity of site extend beyond the capacities of conventional, analog methods. In the digital environment, the model becomes a ground for validation, where ideas are explored risk-free and changes are made more quickly than through the production of physical drawings, scale models, or on-site tests. Because of its centrality to architectural practice, digital modelling as a design method must be interrogated based on two critical concerns: first, the creation of digital models is often driven by a false rationality; and second, digital modelling has an active role in producing urban form that reinforces the profit-driven logics of neoliberal development.

In an age where the production of empirically-derived information is highly accessible, produced at record speeds and quantities, and drives design processes, analyzing and representing data is unavoidable, and more to the point, compulsory. These methods often result in a positivist approach in understanding ecological and social processes. For example, environmental modelling software prioritizes measurable, perceptible data over intangible impressions and interpretations, thus contributing to the troubling assumptions that the inputs and outcomes are objective and created impartially, that they are based on facts, and ultimately that all valuable considerations for design can be primarily drawn from quantitative data. The false rationality of these models means that only those who can be categorized and thus made legible to the logic of the model have the capacity to influence the form of the city.

If the digital model is, as architectural theorist Paul Cureton argues, the container of big data, then it must be interrogated through a critique of technological determinism, the idea that society’s structure and values are established through its technologies. (3) Because it is constructed algorithmically, the digital model is perceived as inherently relational, responding to the shifting parameters of data inputs, which go on to shape visualizations and projections. The digital model has become the method by which data is visually legible and anchored to physical space.

Patrik Schumacher, founding partner at ZHA, has been successful in translating these scripted, parametric models into built work. Schumacher explains what he believes to be the ideal relationship between data and the digital model: “The dream is that you might feed every imaginable factor into a computer, which would then help you deliver a building that harmoniously reflects and responds to all these factors. In this way architecture might base itself on scientific data rather than the intuitive judgments on which it usually relies.” (4) Schumacher’s suggestion that design disciplines should move toward methods that script the built environment using quantifiable data erodes the aspects of the design process which are immeasurable and personal to the specific designer—culture, beauty, and empathy. Design that retains these unquantifiable aspects has the potential to produce unexpected and innovative results that are generated not through the rational output of predefined factors, but through building on instinct, memory, or personal values. The digital model is encoded with assumptions that accept the superiority of scientific epistemologies in addition to the value-based judgments of those who have scripted the model and its simulated environment. (5) It is our responsibility then, as both the makers and the users of the digital model, not to mislead or be misled into believing that it—even with all of its good intentions and perceived precision—will produce a rational and objective design.

For Schumacher, the digital model and its real-world manifestation should be viewed as a strategy for creating “aesthetic order to the visual messiness of the neoliberal city.” (6) He contends that parametricism is the organizing logic needed to structure contemporary urbanism. (7) More than simply an aestheticization of urban life, parametrically-derived urbanism is characterized as a medium in which “all moments of contemporary life become uniquely individuated within a continuous, ordered texture.” (8) Despite Schumacher’s assertion that design is apolitical, the positioning of his role as a producer in charge of arranging urban life is a reminder that political and economic structures cannot be divorced from the creation of physical, material places. (9) Suggesting that parametricism can exist as a modelled totality while also eschewing its ruling politics reveals that this reliance on the model only reinforces the status quo.

Parametric design, according to urban designer Teddy Cruz, is complicit in the urban asymmetry that has resulted from free market neoliberalism. He argues that parametricism has camouflaged the exclusionary politics and economics of urban development through the creation of hyper-aesthetics and beautification. (10) The parametric digital model glosses over the social and political implications of city-making in service of the creation of a form-driven logic that is itself the product of hegemonic biases. The digital model, as a design and representational tool, enacts neoliberalism: it encodes the values of the design model, while the model reciprocally shapes and facilitates the functioning of the neoliberal city. With a focus on performance that seeks an efficient relationship between input and output, the digital model as a design strategy assumes that all relevant and valuable factors can be optimized for desired outcomes. Of course, we know that design is not formed from the rational synthesis of data, however, the digital model prioritizes these quantitative ways of knowing. Architectural historian Douglas Spencer observes that in these digital models of neoliberal architecture, “Our relevance is contingent upon and calculated by our performance as informatic operators.” (11) The popularity of digital models in design disciplines is often justified by their ability to be responsive and flexible to changing data, environmental conditions, and economic realities. Although positioned as significant for the uncertainty of the present world, these qualities are also the defining characteristics of neoliberal economic conditions: a lack of regulation, competition through a self-regulating free market, and an emphasis on individual freedom. It should perhaps come as no surprise that the ascendant method for generating urban designs is entwined with the dominant ideological regime of neoliberalism; however, its role in upholding the inequity and contingency of the neoliberal system must be articulated, interrogated, and challenged to counter the belief that this method achieves a neutral design outcome.

The digital model is already a potent part of our design process—it is a tool whose pervasiveness within the design disciplines will only heighten. As a result, we need to approach it, not as a passive object, but as an instrument that wields power, inscribes meaning, and encodes value. The pretense of rationality and the guise of technological objectivity that the digital model operates within, suggest that its use in design serves to make some lives legible, while others are systematically rendered invisible. Schumacher asserts, “New spatial models must be able to organize higher levels of complexity and integrate significantly more simultaneous programmatic agendas and processes.” (12) Zaha Hadid Architect’s Kartal-Pendik masterplan was never realized, but .the fact that it was awarded first prize in the international competition points to a political and social approach to urban regeneration, one in which cities, in all of their complexity and uncertainty, can be fully comprehended through a digital model, and the algorithm from which it is created. Unless designers make explicit the underlying political agendas of the digital models they produce, the model’s innovative potential will be oriented towards reinforcing the status quo and will continue to create urban form that is inequitable and uneven.

Endnotes

(1) Zaha Hadid Architects, official website. www.zaha-hadid.com/masterplans/kartal-pendik-masterplan/.

(2) Arzu Kocabas, “Kartal urban regeneration project: challenges, opportunities and prospects for the future,” in The Sustainable City VI: Urban Regeneration and Sustainability, eds. Carlos A. Brebbia, Santiago Hernández, and Enzo Tiezzi (Ashurst, UK: WIT Press, 2010), 571.

(3) Paul Cureton, Strategies for Landscape Representation: Digital and Analogue Techniques (New York: Routledge, 2017), 138.

(4) Rowan Moore, “Zaha Hadid’s successor: my blueprint for the future,” The Guardian, 11 September 2016. www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/sep/11/zaha-hadid-architects-patrik-schumacher-blueprint-future-parametricism.

(5) Merritt Roe Smith, “Technological Determinism in American Culture,” in Does Technology Drive History: The Dilemma of Technological Determinism, eds. Merritt Roe Smith and Leo Marx (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994), 2.

(6) Patrik Schumacher as paraphrased by Teddy Cruz, “The Architecture of Neoliberalism,” in The Politics of Parametricism: Digital Technologies in Architecture, eds. Matthew Poole and Manuel Shvartzberg (New York: Bloomsbury, 2015), 190.

(7) Patrik Schumacher, “Historical Pertinence of Parametricism,” in The Politics of Parametricism: Digital Technologies in Architecture, eds. Matthew Poole and Manuel Shvartzberg (New York: Bloomsbury, 2015), 29.

(8) Patrik Schumacher, “The Parametricist Epoch: Let the Style Wars Begin,” in The Architects’ Journal 16 (2010). www.patrikschumacher.com/Texts/The%20Parametricist%20Epoch_Lets%20the%20Style%20Wars%20Begin.htm.

(9) Patrik Schumacher, “On Architecture, Urbanism, Economics, Politics” interview with Patrick Kondziola, Paprika, Yale School of Architecture (2017).

(10) Patrik Schumacher as paraphrased by Teddy Cruz, “The Architecture of Neoliberalism,” 195.

(11) Douglas Spencer, The Architecture of Neoliberalism: How Contemporary Architecture Became an Instrument of Control and Compliance (New York: Bloomsbury, 2016), 119.

(12) Zaha Hadid and Patrik Schumacher, Total Fluidity: Studio Zaha Hadid Projects 2000 - 2010 (Wien: Springer-Verlag, 2011), 26.

Danika Cooper is an Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture at the University of California, Berkeley. Her work focuses on giving expression to underrepresented materials and geographies in the practice, theory, and representation of landscape architecture. Currently, her research explores the relationship between water management, cultural geography, and weather patterns in the world’s deserts.

Zannah Mae Matson is a PhD Student in Human Geography at the University of Toronto where her research focuses on the construction of territory through highway infrastructure development and counterinsurgency doctrine in Colombia. She teaches urban planning and design at Ryerson University. Matson holds a Masters of Landscape Architecture from the Harvard Graduate School of Design.