The Centre Cannot Hold

By Charles Stankievich

Excerpted from 40.1 Perceive

“The centre cannot hold,” writes W. B. Yeats while reflecting on the spiritual ruins of World War I. An archeology of military outposts across the twentieth century unearths a typology of early warning systems that trace the vector of a centre spinning into a “widening gyre.” Such an archeology outlines a series of architectural forms built to function on the edges of civilizations, concretizing a shift from a geometry focused on a centre to a topology of connections. Moving forward through time, traces remain in the form of a trinity of outposts based on three different types of modalities: the sonic in World War I, the visual in World War II, and the electromagnetic in the Cold War. Monument as Ruin (2015), which encapsulates the first two modalities, concludes a three-part research treatise on military architecture in which I have methodologically moved backward in time. In the initial chapter, my fieldwork, Distant Early Warning (2009), engaged with the embedded landscape and the history of electromagnetic warfare in the latter half of the twentieth century. Distant Early Warning investigated how the unique formal overlapping of the functional and structural elements of Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic radome foreshadowed networked warfare as an extension of game theory. The project focused on the geodesic radomes of the Arctic radar surveillance stations as the synecdoche of the Cold War’s development of networked warfare—an architecture that distributes its structural forces through a framework formally related to the communication network connecting the architecture. Monument as Ruin retraces this methodology even farther back by focusing attention on two more, similarly extreme examples of military outposts from before the Cold War: the centre of gravity in the Atlantic Wall comprised of cement Nazi bunkers in World War II and the focus of the paraboloid in British experiments with cement sonic reflectors starting at the end of World War I. Due to their extreme design and construction, the trilogy of twentieth-century military outposts reveal the shift in values of a society from a modernist centre to a contemporary decentralization.

[...]

FROM FOCUS OF PARABOLOID TO CENTRE OF GRAVITY

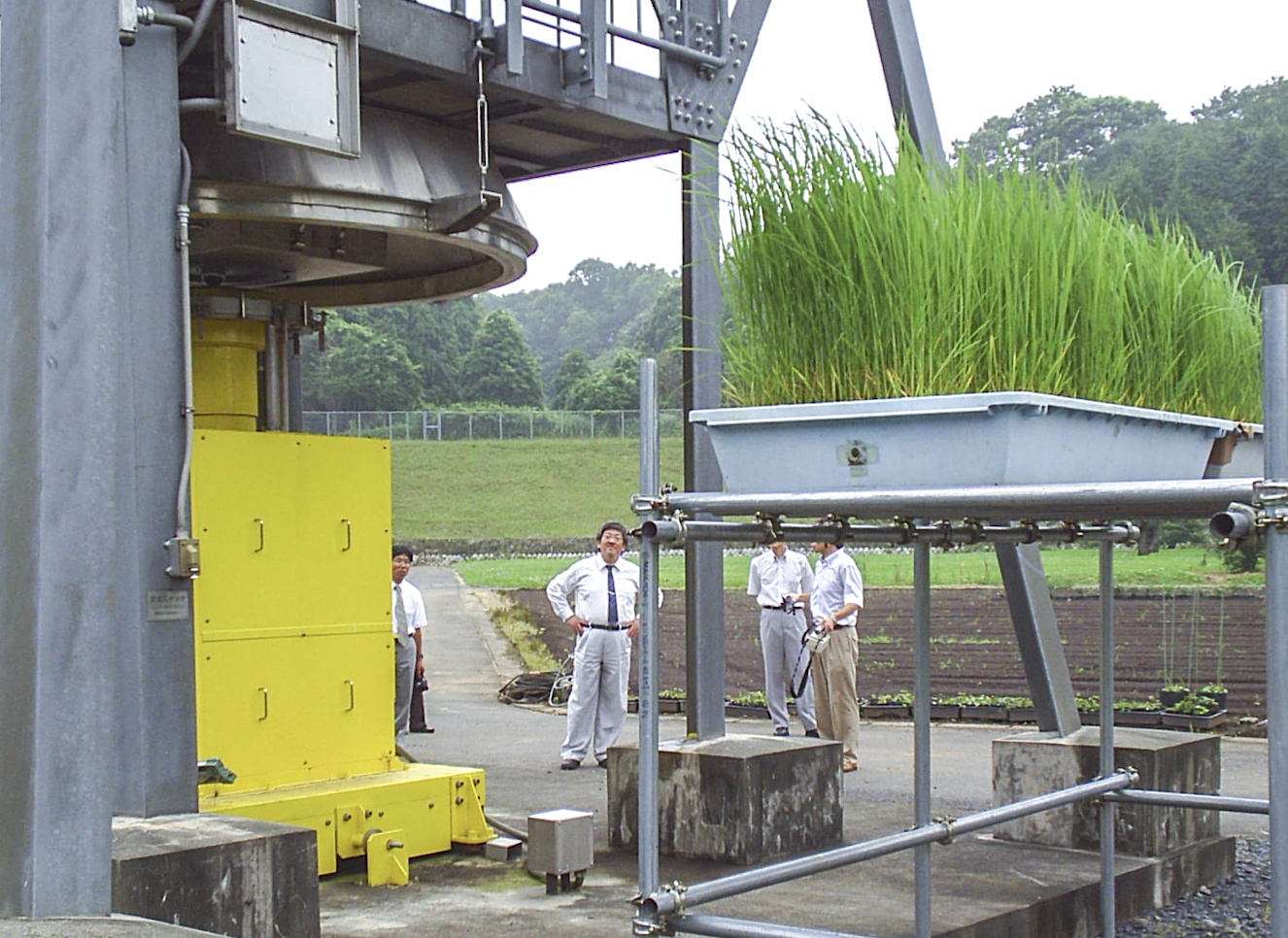

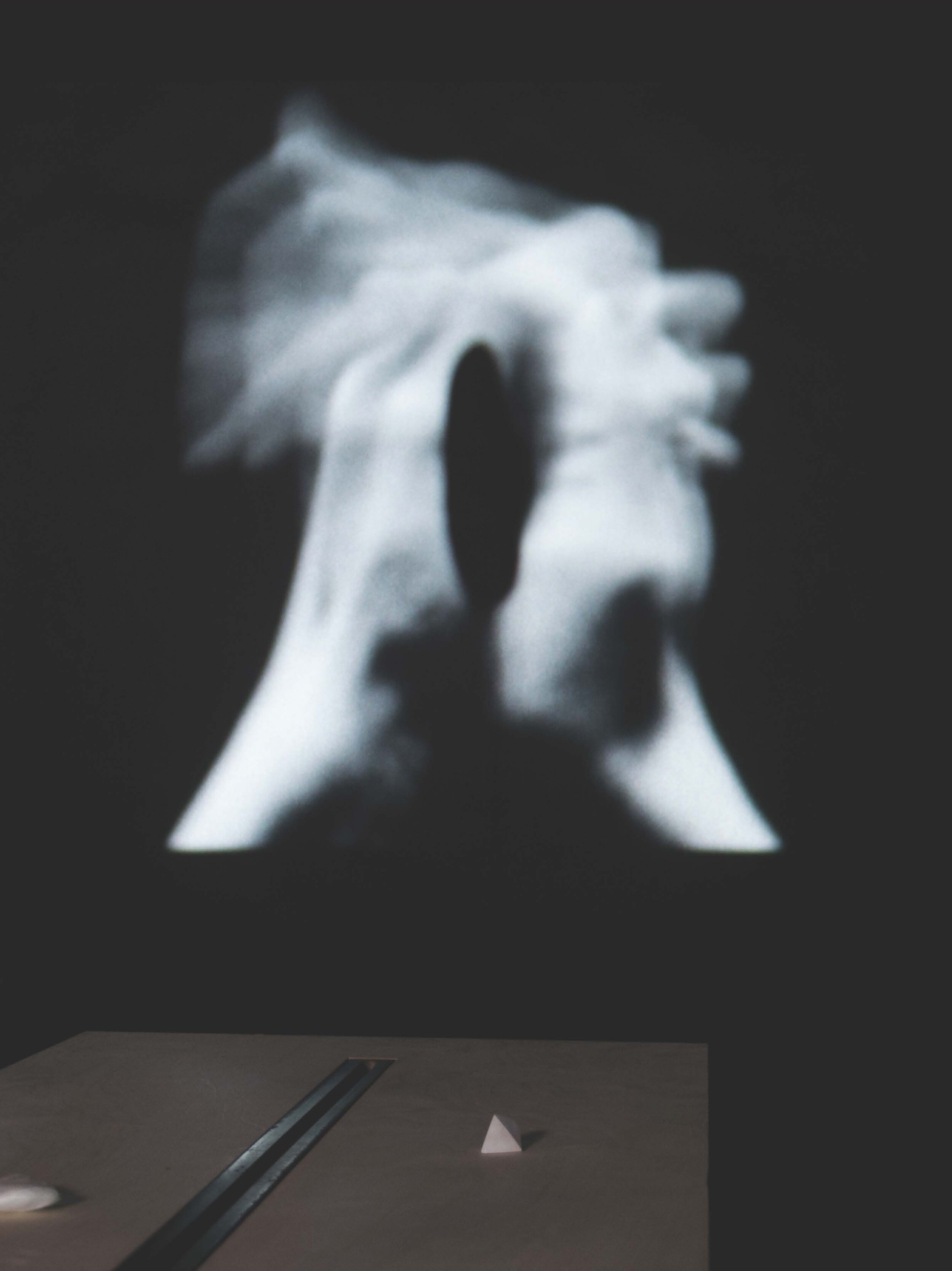

The trajectory of modern military outposts unfolds according to the introduction of the third dimension of warfare—the development of flight that subsequently led to the addition of airplanes to the battlefield. Ancient warfare was at first one-dimensional (or odological, as in linear pathways) as military strategy followed the line of rivers and coastlines from port to port. Advancements in cartography and mobilization established a two-dimensional understanding of war with blocks of territory to conquer and defend. Three-dimensional warfare started to treat the earth, ocean, and air as spaces of penetration. In this modern theatre two elements became important upon introducing aircraft: attack limitations were based on geodetic vectors of distance and not the landscape’s topography, and moreover, the speed of the enemy’s attack became exponentially faster. In order to defend against this new threat, Britain experimented with large cement paraboloid forms designed to collect and amplify the sound of noisy airplane engines. Built on the coast of southeastern United Kingdom as a bulwark against continental invasion, the monoliths’ large concave dishes faced the English Channel, angled slightly upward into the clouds. According to fundamental physics, sound waves were expected to travel across the open ocean/ landscape and bounce off the large reflective surface of the cement dish to be collected at a single point, the focus, and thus amplify the signal. A listener would be positioned at this exact point with either a stethoscope or a microphone, aiming to pick out an incoming bogey. Monumental in size, the structures were immovable, and for most of the paraboloids, so was the resulting focus point for listening. Experiments with later and larger reflectors involved moving the listener or positioning several listeners to attempt a direction-finding technique using spherical rather than paraboloid concaves. Ultimately, the cement forms were a failure as they received too wide a bandwidth of sonic information: from ocean waves and traffic to wildlife and the elusive aircraft. The invention of radar, with its narrowed focus on metallic objects, quickly replaced these experiments before they were of any practical use, other than the establishment of a network protocol between outposts that was transferred to the Chain Home system. (Ironically, the first radar experiments by the British included bouncing a BBC radio signal off a bomber—a direct transfer from sonic to electromagnetic information.) Today, the paraboloids stand guard over a Tarkovskian Zone of overgrown marshes, fields, and ruins. We no longer know if these monolithic sentinels are still listening. Perhaps, like the monolith of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, they are waiting to send out a cosmic signal at the destined geological period, although in our parallel universe, not at the advent of galactic Homo sapiens but after the Anthropocene when the Earth has cleansed itself of the dangerous mutations of humans.

[...]

The full version of this essay appeared in -SITE 40.1: Perceive. It was originally published in the exhibition catalogue for The Centre Cannot Hold at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in 2015.

All images courtesy of the author.

Bio

Charles Stankievech is a Canadian artist whose research has explored issues such as the notion of “fieldwork” in the embedded landscape, the military industrial complex, and the history of technology. Since 2011, he has been co-director of the art and theory press K. Verlag in Berlin. He is currently an Assistant Professor in the Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design at the University of Toronto.