The Distance of the Tactile

By Thi Phuont-Trâm Nguyen

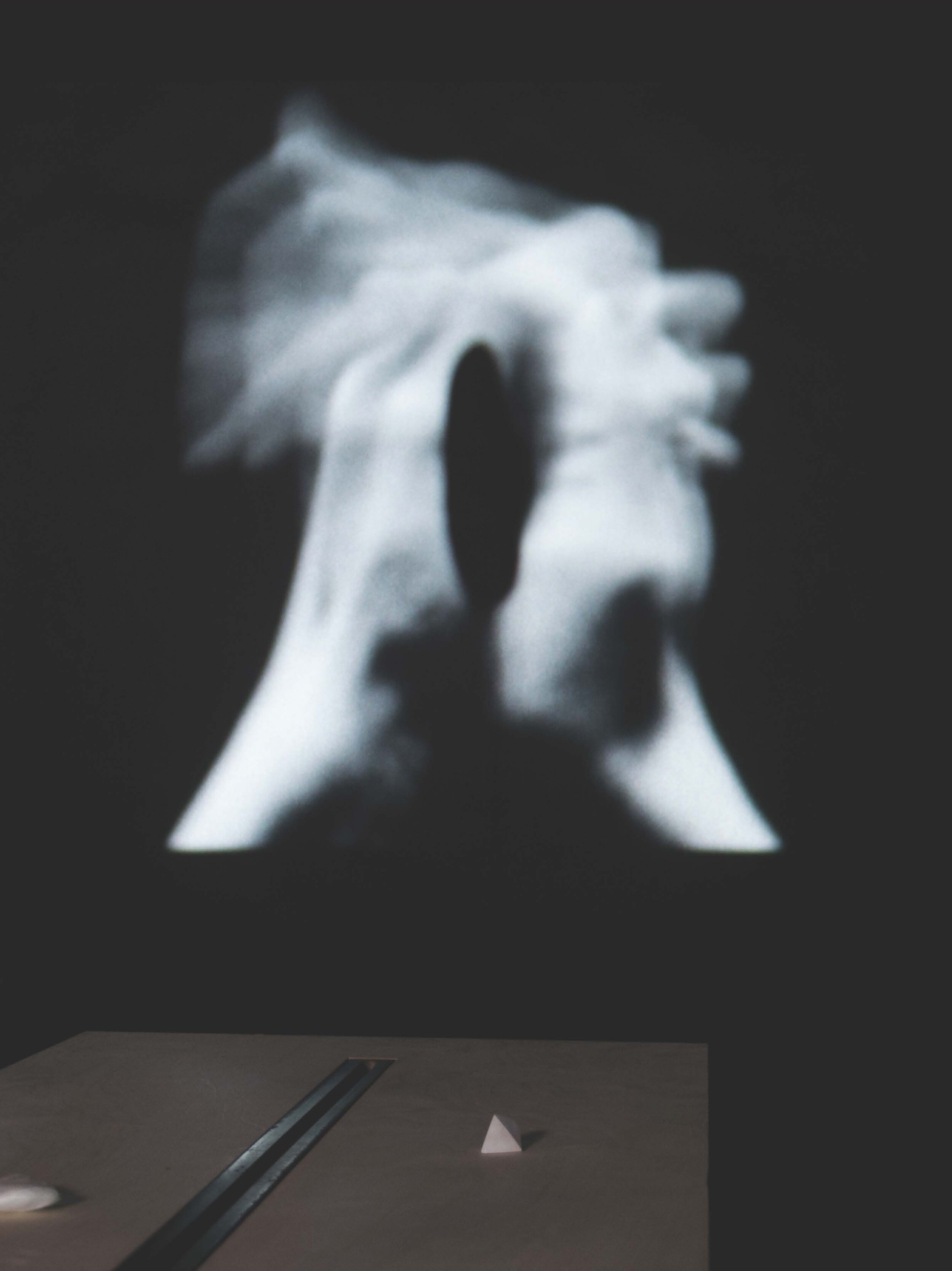

The following work—part drawing, part narrative—is a visual essay about the ineluctable distance that links the acts of looking and drawing. The images stem from research on the potential of anamorphic images and their technique to question the relationship between the real and the imagined.

Anamorphic drawing evolved in parallel with the development of perspective in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; however, it did not seek to represent the appearance of space as accurately as possible. Instead, it used the same geometric principles as perspective and carried them to an extreme to create a break between the real and the represented. To achieve this, the images were constructed in reference to a focal-point that had been displaced closer to the distance point. As a consequence, image resolution was only possible when the observer moved to a specific point in space. In this shift, the depth of the image emerged. No longer recessed in the picture plane, it was experienced in front of it. If perspectival construction is a perpendicular plane in front of the viewer, then anamorphic images consist of a diagonal cut through the cone of vision that allows access to the space of perception. While perspectival drawing as a device for the architect is ingrained in the profession as a means by which to propose an imagined project to clients and users, the relevance of the study of anamorphic drawing lies in its capacity to reflect on the space in front of the picture plane. In Picturing Space, Displacing Bodies, the art historian Lyle Massey puts forward that “anamorphosis posits an embodied viewer who cannot escape contingency, temporality, and performativity.” [1] The narrative, previously contained within the picture plane in perspectival images, is now experienced live in space—in the present. Between the appearance of one image and the apparition of another, the fictional space of representation coalesces with the present space of the spectator. Following this idea, this project focuses on the gestures of drawing where the two realms meet rather than on the drawing itself. The images propose a narrative in the space where vision takes place.

Using a model as well as photography and the projection of moving images to expand the space of vision, the work originates from the writings of Jean-François Niceron. His treatise La Perspective curieuse, written in 1638 and republished in 1663, is dedicated to the construction of anamorphic images. In his book, Niceron details a mural apparatus with a hinged frame containing the image to deform and a marking system of treads and weights. The device implies a continuous back and forth from the primary image to the displaced secondary plane. This repetitive movement emphasizes the distance between the fix position, where the primary image is visible, and the displaced plane where another image appears. The method expands the depth of the image, blurring the boundary between what we see and what we are looking for. The anamorphic image can be delineated by following the projected threads, which act as the rays of vision, from one plane to the other. To ensure the accuracy of the prolongation of the line of sight from one plane to the other, the system requires the adjustment in the threads’ tension. By deceiving vision and breaking with the initial view, there is a return to the sense of touch as a way of understanding the limit of the image. The shift between planes is both a change in position and a change in perception.

The two images—the one that lies, distorted, against the picture plane and the one that emerges into space when the viewer steps into position— cannot exist simultaneously. Latent within each other, the full meaning of the image can only be revealed by the movement of the observer. The sequence of work, projecting, reflecting, and scattering, transfers the image from one plane onto another, piercing and marking it with light and charcoal. In wavering in the thick of what is present and what is possible, the nature of the drawings created presents a sense of hesitation, an uncertainty of scale and subject. In a return to Massey, “anamorphic distortions make the viewer aware of phenomenal as well as representational space.” [2] The images extracted from film, projection, and installation capture the texture and process related to the temporality of the discovery of the anamorphic image. The delineation of an anamorphic image resides in the realm between seeing and sensing, caught between the desire to grasp something and the impossibility of reaching towards it. The work remains unfinished, never quite there.

All images courtesy of the author.

Endnotes

[1] Lyle Massey, Picturing Space, Displacing Bodies: Anamorphosis in Early Modern Theories of Perspective (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2007), 68.

[2] Ibid, 67.

Bio

Thi Phuong-Trâm Nguyen is a trained architect in Canada and holds an MA in Architectural History & Theory from McGill University. She is teaching at the Azrieli School of Architecture and Urbanism while also pursuing a PhD in Architectural Design at The Bartlett School of Architecture (UCL). Her research, “Anamorphosis | Drawing Spatial Practices,” addresses the temporality of the gesture of looking through the study of anamorphic construction. Her design work explores the possibilities of drawing, filmmaking, and writing to occupy the space of perception.