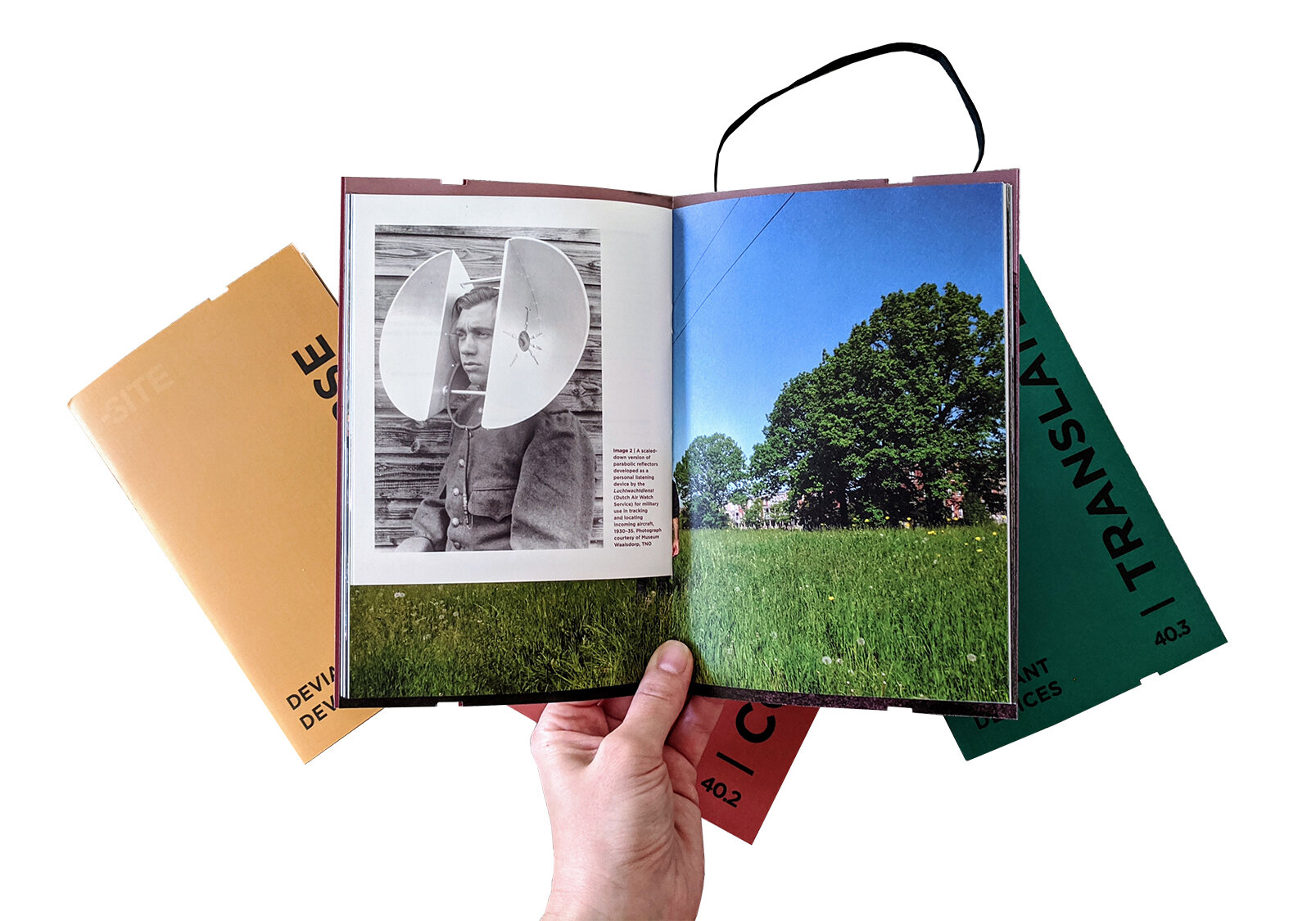

Productive Devices

Aisling O’Carroll in conversation with Mark Smout, Laura Allen, & Geoff Manaugh

An excerpt from Volume 40.2 Collect

In July 2019, The Site Magazine editor Aisling O’Carroll sat down with Mark Smout, Laura Allen, and Geoff Manaugh to discuss their ongoing collaborative work in the space between architecture and landscape, where they design, prototype, and narrate future histories through architectural scenarios. Together, the three have collaborated on a variety of projects ranging from research to teaching, exhibitions, and design work. They discussed the role of narrative in shaping an approach to design and the trio’s fascination with the design of devices as a way of framing new readings of, and engagement with, landscape.

AISLING O’CARROLL (AO) | Maybe we can start from the beginning— how did this ongoing collaboration between the three of you begin?

MARK SMOUT (MS) | When BLDGBLOG started it was a particular moment for us. In the way that Laura and I were taught about architecture there was a lineage in thinking about work not just as a construct but as a longer, thinner story that wrapped around objects and carried through drawings. We were looking at Peter Cook and Alvar Aalto, Enric Miralles and Lebbeus Woods. And when we came across BLDGBLOG—we were teaching at The Bartlett at that point—we realised that someone had written all this stuff down and formalised it in a kind of way. It was like that brain had been emptied onto a blog and it was tantalizing.

We met then for the first time when Geoff invited us to talk about The Retreating Village, shortly after the Pamphlet came out. [1]

Image 1 / L.A.T.B.D. “Drift City” (foreground) and “Slow Fountains” (background), installation at Doheny Memorial Library, University of Southern California, 2015. Photograph courtesy of Smout Allen

GEOFF MANAUGH (GM) | Yes, it was back in the summer of 2008 when we first physically met. That kicked off a friendship and a collaborative working relationship—of variable animosity. (laughter)

There were two main things that really attracted me to your work. One of them was the narrative sense that you carried through your projects: you would take a scenario based in something materially real and scientifically verifiable, something that could just as easily have served as the basis for a short story or an article—like The Retreating Village—but instead you turned into an architectural project and generated a design proposal. There was also your way of working with devices, like dioramas or spinning landscape models—devices taken from science, art, and even the entertainment industry for representing and studying landscape—that you brought into the context of architecture. That really changed how I look at modelling landscape: the device is an architectural landscape model but, at the same time, it’s also a tool for studying and changing spatial perception.

Image 2 / L.A.T.B.D. “Earth Observatory,” installation at Doheny Memorial Library, University of Southern California, 2015. Drawing by Smout Allen

[…]

LAURA ALLEN (LA) | Architects tend to secrete so many agendas in their work, but if you’re doing something that’s instrumental, you can’t really do that, you have to think about it in a completely different way. And so, when we work more architecturally, it’s often halfway between those things: secret stories that get you working through your projects, and other things that actually are a demonstration of the tool.

MS | Yes, taking things up to the stage of a prototype is actually the most exciting part, isn’t it? I’ve got a set of photos of the NASA Skylab mock-up. It’s a 1:1 built model and there’s a bunch of people in there pretending to be astronauts and a picture of what they thought the earth—the blue marble— might look like through the window. And their door is made of paper. It’s fascinating—you can see how much is worked out and revealed about the Skylab environment through the prototype.

Sometimes the notion of the device can be just as clearly expressed through a drawing or model. We make models that you can turn, you can touch and play with. We’re not bothered about people touching stuff. The things we do are all meant to be quite accessible—to both children and adults.

AO | That engagement means you must also be open to the various interpretations that would come from everyone bringing their own perspective.

LA | Absolutely. That’s the next level of testing, isn’t it? When something is misinterpreted or reinterpreted by somebody else.

GM | It’s useful to look at this in the context of theoretical physics versus experimental physics, for example. In other words, a person working in either field can be pursuing the same basic questions about gravity, or atomic energy, or whatever it might be, but one of them is actually designing machines that can split the atom, or extract heat from a vacuum, while the other is coming up with the theory and the equations to explain it. It’s interesting to think about architectural devices in that same way: you’re trying to actually make something that will physically perform a spatial act. In the context of the stuff we do, it’d be a little weird if the end goal was only to make and prototype working devices that we could ship, patented and trademarked, to a construction company. It’s more about creating a device as a question or using a device as a way of reframing an investigation so that other people can then use that device as a lens to ask further questions themselves.

LA | We made the devices for the River Severn work, but what was more interesting than seeing them function was how uncomfortable they made people feel when we were using them. We made two things, called the Drip and the Sniff, to look at the flora and fauna along the river in a new way. We placed them in fields next to the river. One of them was sucking in water from the river, while the other one looked at the quality of air around the river.

MS | We set them up, unwittingly, right next to the Hinkley Point nuclear power station. They were great, but they made people feel uncomfortable because of the nuclear power station right there.

Image 3 / Observations of the Ballistic Instruments were read to inform strategies for architectural concealment and revelation. Their performance is interpreted in backlit “paintings” where a balance of projected and reflected light and subtle gradients of colour are revealed within the black silhouette. Ballistic Instrument painting. Photograph courtesy of Smout Allen

LA | People didn’t like it. They started asking what’s happening? What are you sniffing that we don’t know about? By just making a machine that sniffs the air, it made people start thinking, “What does that air contain?”

AO | So in that context, by placing the device there, it made people much more aware of their surroundings and question things that were probably there all along.

LA | Yes, otherwise they were living quite happily there. I don’t suppose they’ve got themselves little Geiger counters in their doorsteps, they probably should!

[…]

GM | [Devices] introduce this idea that there is something present around us right now; we’re in it, and we’re part of it, but we don’t know about it until this device arrives. And then we realize, my god, there’s radiation here, or hidden magnetic fields, or a gravitational anomaly caused by a buried archaeological ruin we otherwise wouldn’t see.

Image 4 / The Drip, Envirographic Instrument with Hinkley Point, 2010. Photograph courtesy of Smout Allen

LA | Once we began looking at the data and information generated by devices we started considering how we could make that information meaningful, or filter it in a way that allowed particular stories to come out of it. There are two things: one is about making something visible that is otherwise ephemeral or emerging and not yet in other people’s consciousness. And the other is about the proposition: How do we physicalize the ideas that come out of the research?

Most of what we try to do is to physicalize those things. It’s why quite a lot of the work on many of our projects is a bit analogous—we make a model, or an architectural proposition, that is analogous to parts of the system we are observing. We are often exploring how an architecture can manifest the invisible layers of an environment or the processes working there that are made visible by new ways of seeing.

GM | The communication and representation of a project is itself a kind of device. One of the things that would be interesting would be to revisit some of the projects, like The Retreating Village, but to look at ways to remake it cinematically. I’m obsessed with the idea of getting an architecture project optioned for film, and I feel like it could happen with that project, if done correctly, offering a whole new frame for understanding the site and project.

MS | That would be fabulous, The Retreating Village 2.0.

Image 5 / Surface Tension is a large interactive installation that simulates the undulations, waves, droughts, and surges of the planet’s hydrological cycle. Surface Tension, Landscape Futures exhibition, Nevada Museum of Art, Reno, Nevada, 2011. Photograph courtesy of Smout Allen

The full version of this interview appeared in -SITE 40.2: Collect.

NOTES

1/ Smout Allen, Augmented Landscapes, Pamphlet Architecture 28 (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2007).

2/ Barbara Maria Stafford and Frances Terpak, Devices of Wonder: From the World in a Box to Images on a Screen (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2001); quoted in Geoff Manaugh, “Landscape Futures,” in Landscape Futures: Instruments, Devices and Architectural Inventions, ed. Geoff Manaugh (New York: Actar Publishers, 2013), 25.

Bio:

Geoff Manaugh is a Los Angeles–based freelance writer and the author of the New York Times bestselling book A Burglar’s Guide to the City (2016). Since 2004, he has also been the author of BLDGBLOG (bldgblog.com), covering topics related to architectural conjecture, urban speculation, and landscape futures.

Mark Smout and Laura Allen jointly run the design research practice Smout Allen, where they explore the intersections and interactions of landscape, architecture, art, and science. They are both professors at The Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL, where they run a diploma studio, Unit 11, in the Architecture MArch program and direct the Landscape Architecture degree programs. Since 2010 they have regularly worked in collaboration with Geoff Manaugh, developing projects including L.A.T.B.D. for the Chicago Biennial and University of Southern California and the “British Exploratory Land Archive” for the 13th Venice Architecture Biennale.