New England Accent

By B. Cannon Ivers, Devin Dobrowolski & Mary Catherine Miller

Vernacular construction occurs through the application of embedded, localized knowledge developed over time and through custom. When applied to architecture, the term describes the evolution of urban fabric and building typology based on spontaneous, rather than critical, evaluation. (1) It’s tempting to apply a similar reading of landscape, acknowledging its own inherently constructed nature. Yet doing so may signify a false equivalency between the two as separate products of a similar process of cultural activity.

Recent critical discourse in landscape history has addressed the complex etymological provenance of the term “landscape” in an attempt to re-evaluate and clarify its contemporary usage and meaning. Perhaps the most salient work on this subject comes from J.B. Jackson who, in his book Discovering the Vernacular Landscape, provides a concise, modern definition of landscape as “a composition of man-made or man-modified spaces to serve as infrastructure or background for our collective existence.” (2) To define landscape in this way reveals the extent to which its construction, as both a concept and a physical environment, is the result of a mixture of environmental and cultural conditions.

Despite attempts to define and condense the experience of landscape through language, its imbricated layers of climate, geography, and topography, along with temporal fluctuation of human occupation, seasonal, and diurnal variations, highlight the complexity and ambiguity of the task. Nevertheless, the ability to identify the visual and corporeal singularity of specific landscapes is undeniable, and this is what we can define as a landscape vernacular, which is both related to and distinct from architecture because of its territorial scale and relationship to temporal phenomena.

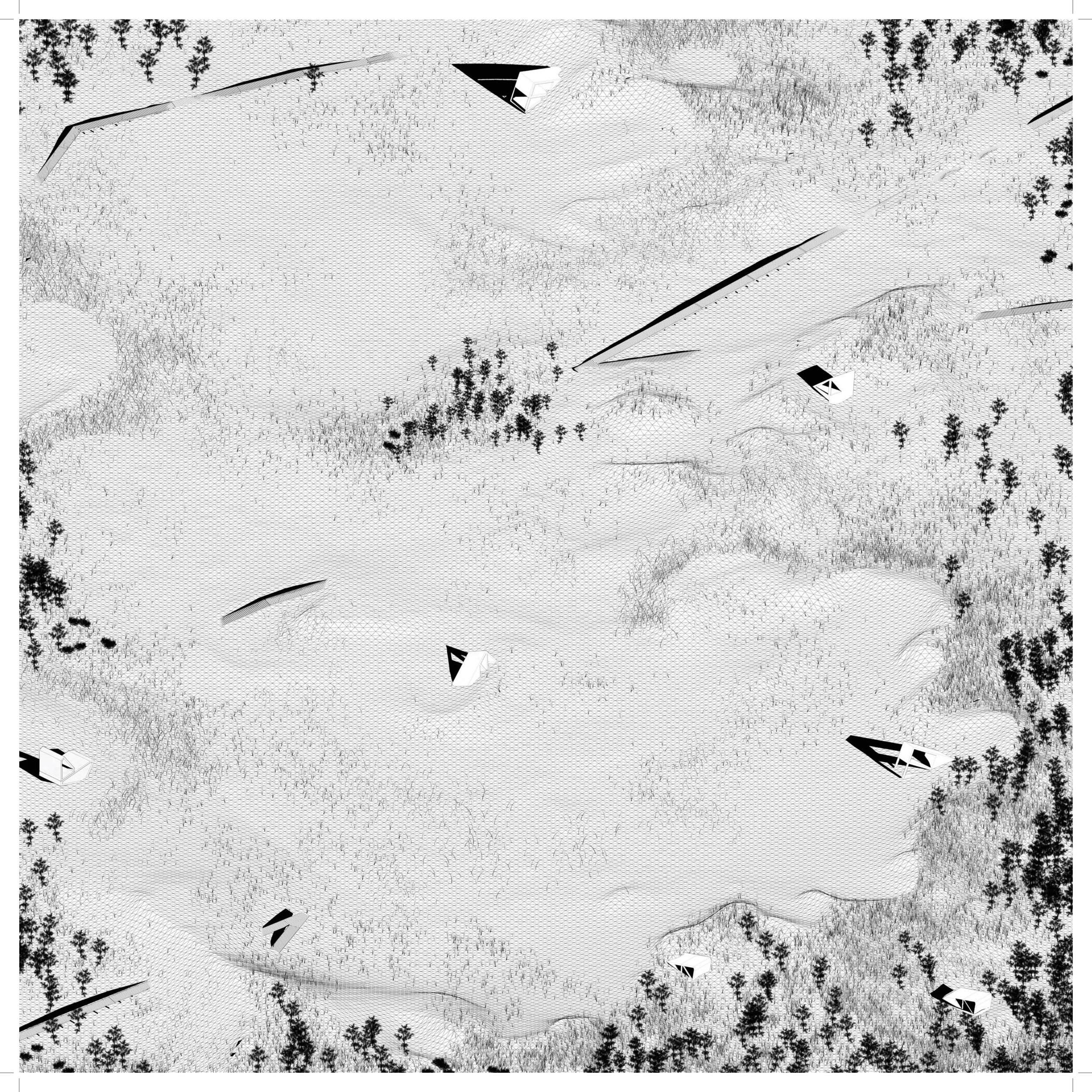

As a case study in vernacular North American landscapes, Cape Cod is a region with deeply embedded historical and cultural associations. It evokes images of shifting sand dunes with wind-swept grass, salt marshes in myriad colours with rich tones, textures and the familiar call of soaring seabirds. It conjures postcard images of imbricated white cedar-shingled houses, clam shacks, boardwalks, cranberry bogs, blueberry patches, and cultural icons such as the Kennedys (See Image 1). As such, the vernacular construction of Cape Cod (the place) is inextricably tied with Cape Cod (the idea).

Yet, this is a treasured landscape that runs the risk of vanishing. Presently, the number of healthy and functioning salt marshes is in steep decline and the spectre of climate change is altering both the shoreline and the culture of the Cape. Insurance policies are becoming increasingly more difficult and expensive to renew as storm surges eat away at precious beachfront property, parking lots, roads, and even the beaches themselves.

Visible ecological changes are also occurring independent of sea level rise. The accelerated loss of wetlands along the eastern seaboard, especially in New England, has been tied to overfishing. Within Cape Cod Bay, recreational fisherman have greatly diminished the population of predators like Striped Bass and Dogfish that feed on the purple marsh crab, Sesarma reticulatum. While the crab is a native species, it is also a rapacious herbivore that feeds almost exclusively on Spartina alterniflora (smooth cordgrass). With fewer predatory fish occupying tidal regions, the crabs multiply unchecked within mudflats and along the banks of salt marshes. (3)

The Spartina is the backbone of the marsh, reinforcing its muddy banks and buffering against the ebb and flow of tides. With the banks denuded by crabs, tides take their toll and the marshes quietly acquiesce to the ocean to become barren patches of mud. The rate of erosion in these once healthy ecosystems is concerning, both ecologically and visually, blighting the picturesque shores of the Cape that were once replete with a colourful patchwork of grasses, sedges, rushes and perennials.

Yet another ubiquitous mark on the Atlantic salt marshes is the gridded network of one-metre-wide ditches commissioned by the Works Public Administration (WPA) as one of President Roosevelt’s New Deal initiatives. (4) As a means of job creation, the project put people to work excavating channels intended to encourage drainage of stagnant water to combat mosquito-borne illnesses. A recent intensive effort by ecologists and hydrologists aimed at reconstructing the marshes has enabled some measure of recovery. However, the legacy of the ditches has already altered the ecological composition of the salt marshes. The failure of the program as a means of mosquito control is exacerbated by its success in extending the habitat of the burrowing, shoreline-dwelling marsh crabs. With an orthogonal geometry largely inaccessible to any fish or other would-be predators, the ditches multiply exponentially the conditions necessary for the crabs’ proliferation. As a result, formerly saturated tidal regions rich with vegetation, wildlife, and invertebrates have become muddy landscapes with an altered vegetal matrix and a greatly compromised ability to absorb and buffer the effects of storm surges.

The Great Marsh in Barnstable, Massachusetts, which looks north across Cape Cod Bay, is one of the largest and healthiest remaining salt marshes on the East Coast. This is due largely to the fact that it is protected by a 10 kilometre barrier beach fed by marine and river sediment transported by the eddying current of the Atlantic conveyor. The common perception is that the dune landscape of this extensive barrier beach is a fragile and threatened habitat that should remain devoid of human activity for the fear of vegetation loss and concomitant erosion. While this may be true in some areas, there are other factors affecting an even greater percentage of the dunes. To develop practices that will ultimately preserve the dunes, it’s important to understand how the landscape of this region has transformed over the previous centuries.

The iconic dunes of Cape Cod are a relatively recent addition to the shoreline that developed as a result of the clear-cutting of indigenous forest by European settlers in the 17th century for farmland, building material, and fuel. In doing so, the settlers destabilized the existing topsoil, exposing the underlying Aeolian sands deposited in the last ice age. Left unchecked, the dunes will follow the natural process of reforestation that has already occurred in much of New England, but managed disturbance may be a radical and effective approach to preserving the dunes, which have become the very essence of the Cape’s vernacular and site-specific landscape condition.

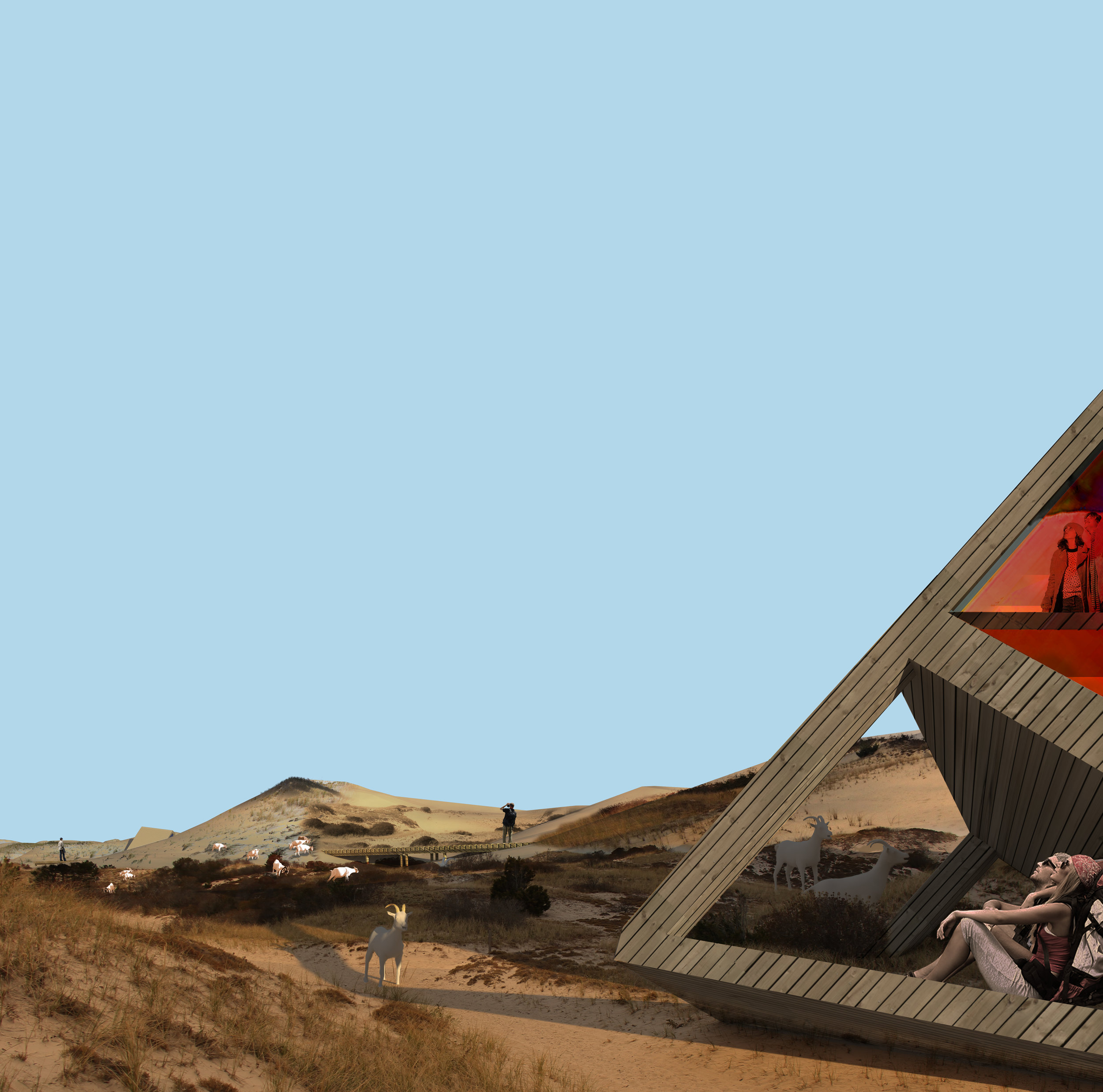

In a challenge to traditional ideas of landscape preservation, Wanderers, proposes alternative forms of touristic activity aimed at preserving the dune landscape of the Cape Cod National Seashore through the lens of managed disturbance. The project challenges the perception that this peripatetic landscape is fragile by expanding the opportunities for people to access and experience the landscape and contribute to the already unpredictable movement of multiple agents that shape the dunes: the constant shifting of sands, the rising and falling of tides, and the rhizomatic distribution of vegetation across the landscape.

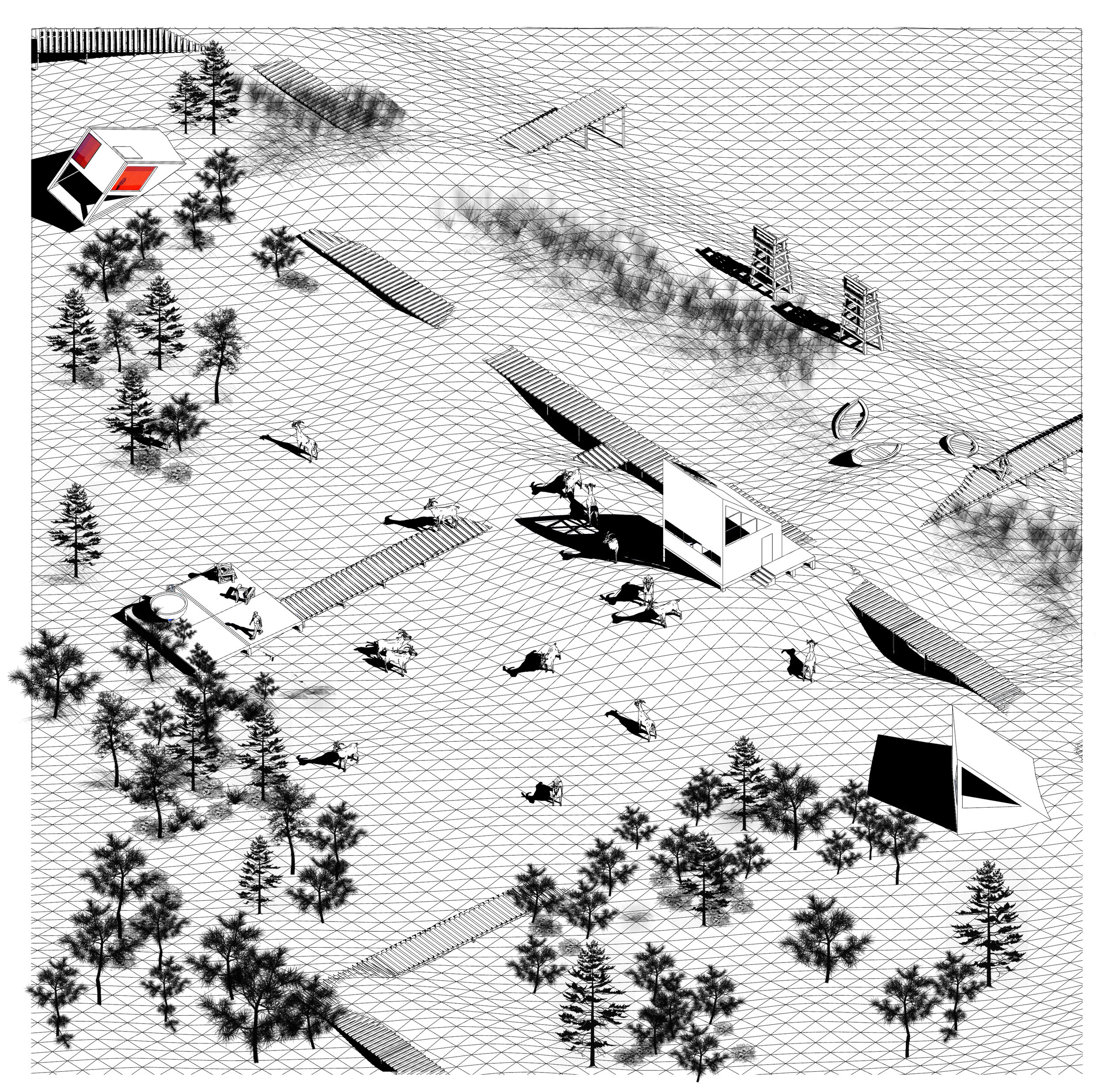

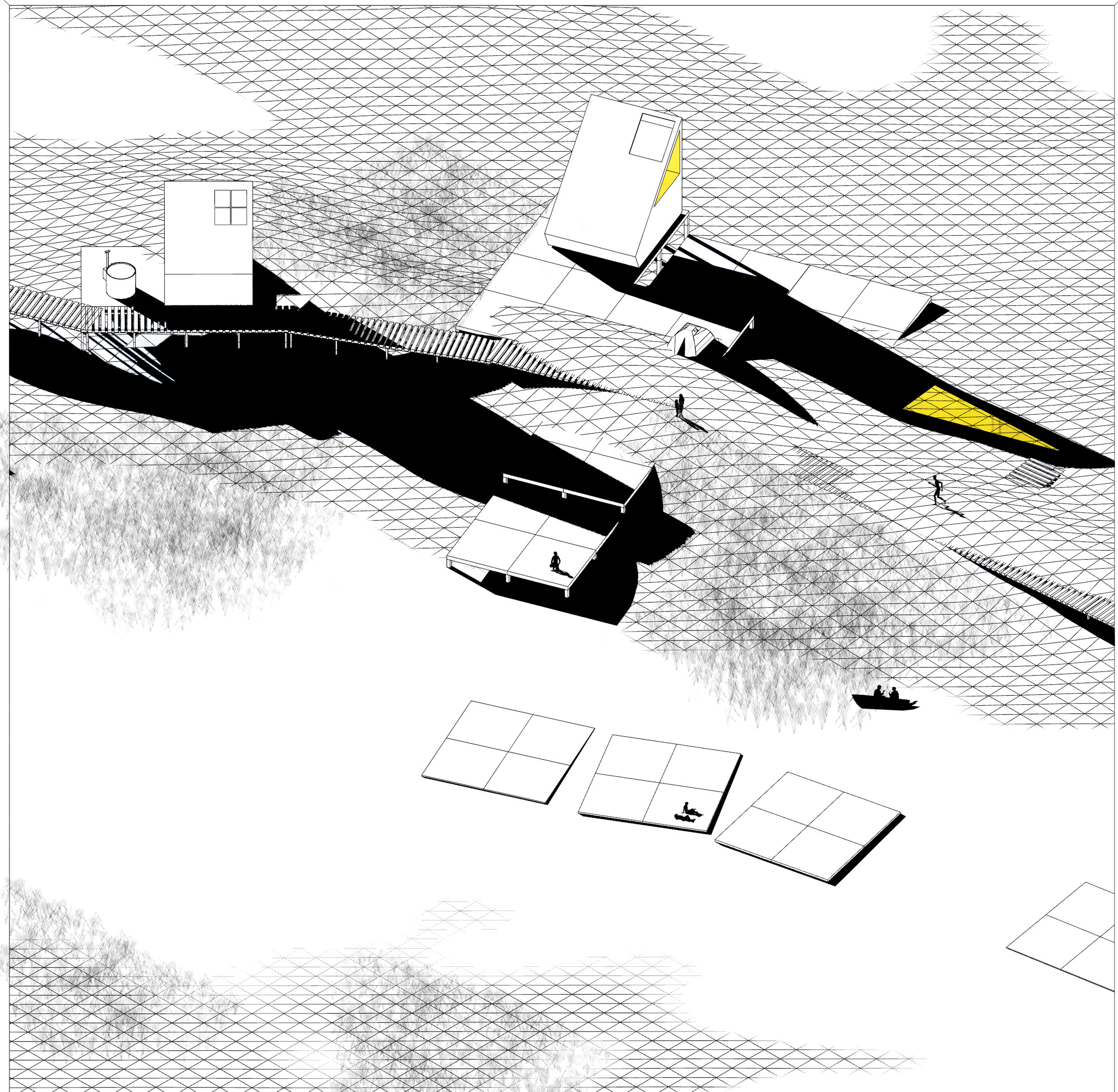

Sited along the Great Neck barrier beach, the proposal frames tourism as an agent and key player in the strategy to intervene and participate in the languid, drifting morphology of the dunes. As an alternative to conventional beachfront hotels or roadside motels that are removed from the coastal elements that make this region unique, the proposal introduces a model of unfixed, ‘wandering’ structures that move seasonally with the dune landscape and rise and fall with the daily cycles of tides within the salt marsh. These nomadic structures could be temporarily occupied by visitors for a week, a night, or just a few hours as retreats of total isolation and solitude, hideaways for creative endeavour, artistic invention, or restful introspection.

The study site for the project is located 5 kilometres from the nearest car park, reinforcing the overarching ambition to create an experience of total immersion within the landscape, urging intrepid visitors to hike deep into the dunes and discover the itinerant structures (See Image 2). A network of fixed boardwalks situated around the structures is repeatedly buried and revealed by shifting sands, exposing the reality that this is a landscape in constant motion while also serving as temporary visual landmarks and itinerant follies. At the mouth of the marsh, tethered structures rest on the shores at low tide alongside oyster trays and crustaceans. As the tide rises, the structures become floating decks, moving gently with the currents for hours before again resting on the marsh bed as the ocean recedes.

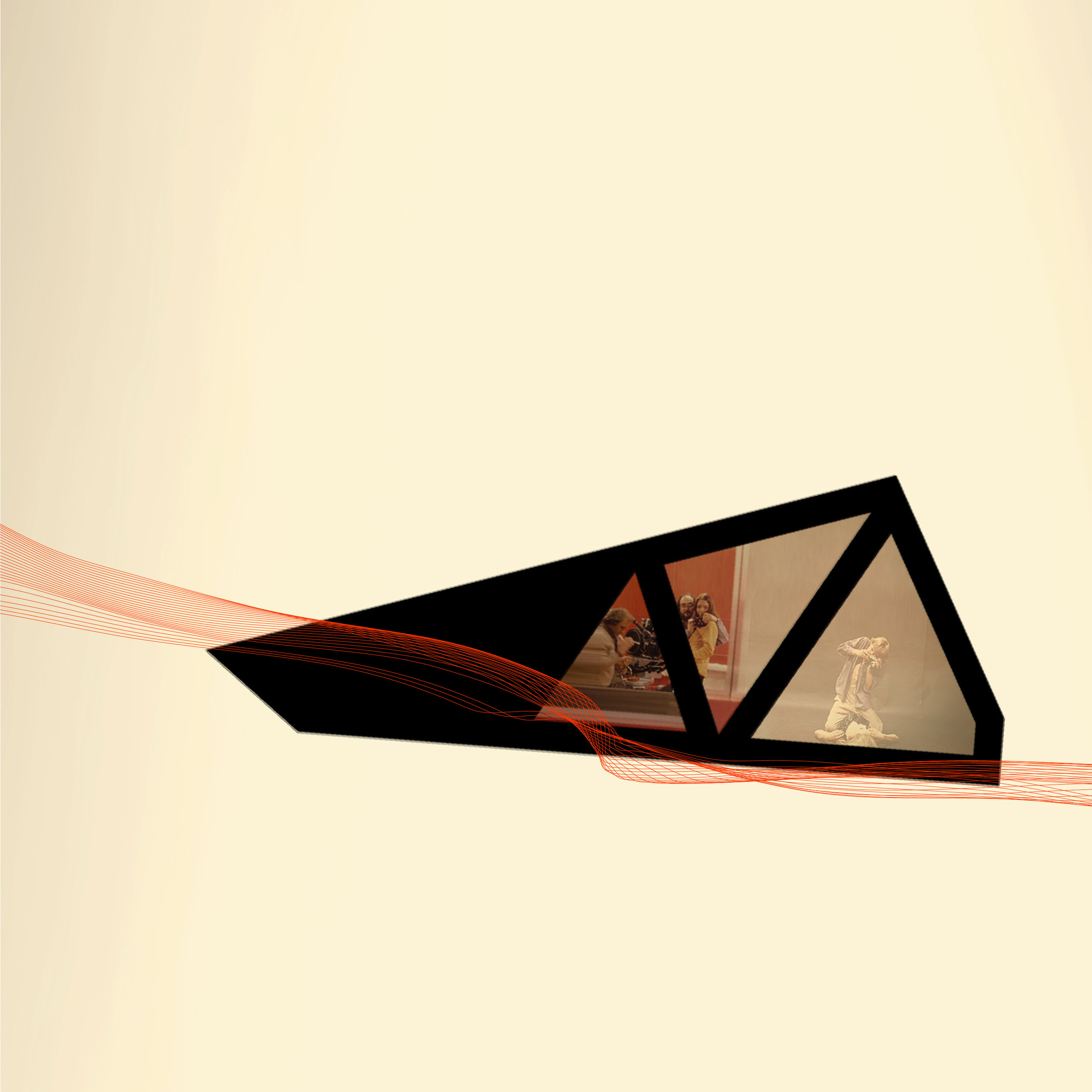

The design process began by exploring the morphological processes of dune formation and movement. Using computer-aided milling, a 1.2 metre by 1.2 metre physical model was created from the digital superimposition of two frozen moments in the process of dune migration. Lines indicating vectors of wind cut through one 3d topography to reveal the nascent dune formation below. The parallax effect of the model lends a sense of animation to an inanimate object. A laser level was used as a method for quickly generating sections through the model to register the topography and hypothesize on microclimatic conditions, water attenuation, and subsequent areas where vegetation would establish (See Image 3). With an understanding of the morphological conditions, a notation language was developed to explore abstractly and diagrammatically the conditions, potentials, and outcomes for human activity and occupation that could be applied to the site while avoiding the specifics of form and composition (See Image 4-5).

This design process enabled a fluidity of experimentation that responded to the unpredictable conditions of the site. Using a 1.2 metre by 1.2 metre lightbox with one metre contours and existing vegetation printed on transparent acetate, ‘game pieces’ were configured to develop layout options for the deployment of foundationless structures in the dunes and fixed boardwalks at strategic positions adjacent to existing footpaths (See Image 6-9). The notation studies prioritized flexibility over fixity, responding to the site rather than imposing a static configuration.

The rugged beauty of the dunes is an iconic and integral part of the vernacular landscape of this region—one that is certainly worth preserving. However, in treating the dunes as an artefact, they will almost certainly disappear. At its core, Wanderers aspires to facilitate a visceral connection with the vernacular landscape by encouraging new types of touristic activity within previously restricted lands. Fundamentally, it forces questions about the degree to which the landscape, along with the economies and customs associated with it, must remain fixed or whether we can design a process to facilitate changes that allow for contemporary uses to coexist with established histories and customs.

The sounds of wind-stirred dune grass and sand racing over slopes are characteristics of this landscape that must be experienced to be understood. Wanderers is a project that encourages an ongoing engagement with the landscape by tapping into its temporal rhythms. The catalogue of structures, boardwalks, and tent platforms respond to the landscape and contribute to the processes that shape it. Fixed boardwalks that once linked directly to a structure might later lie half buried by shifting sand, changing the very idea of the pathway and challenging the function of the boardwalk (See Images 11-15). The experience of visiting and revisiting a landscape in constant motion registers the passage of time and makes visible natural phenomena that is otherwise largely imperceptible.

Wanderers is based on a Romantic idea that draws from a history of the sublime and beautiful dynamism of landscape to propose ephemeral touristic practices in which built form becomes a device for measuring time and registering natural phenomena. The project calls into question what should be preserved and how to adjust to ecological, environmental, and economic change. It is a process that privileges formation over foundation (See Image 16,17) and positions landscape as an active agent in shaping the future of the Cape Cod National Seashore and its unique North American vernacular.

Endnotes

(1) Gianfranco Caniggia and Gian Luigi, Architectural Composition and Building Typology: Interpreting Basic Building (Firenze: Alinea, 2001).

(2) John Brinckerhoff Jackson, Discovering the Vernacular Landscape (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984), 8.

(3) “Crab-driven vegetation losses.” National Park Service, Accessed September 2014, https://www.nps.gov/caco/learn/nature/crab-driven-vegetation-losses.htm

(4) The “New Deal” was a collective name for a series of social and economic stimulus initiatives implemented during Roosevelt’s presidency under the Works Public Administration.

B. Cannon Ivers graduated from the Harvard Graduate School of Design with distinction. Throughout his professional experience in the field of landscape architecture, he has been awarded numerous awards, collectively and individually, for innovation and execution of high quality public realm projects and contemporary urban parks. He is a chartered member of the Landscape Institute in the UK and a Director with LDA Design in London.

Devin Dobrowolski holds a Master of Landscape Architecture degree with Distinction from Harvard Graduate School of Design. He is currently a candidate for a Master of Architecture degree from Princeton University. Prior to joining the fields of urbanism and design, Devin worked as a documentary and environmental filmmaker.

Mary Catherine Miller completed her Master in Landscape Architecture degree at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design in the spring of 2016. She is currently pursuing a Master in Design Studies degree with a focus in Energy and Environments at the Graduate School of Design. Her research stems from a collaborative project: Wild Interfaces, with Joseph Watson. This multimedia exploration of conservation, connectivity, and landscape architecture is the seed of Mary's research, which shifts across scales and mediums to explore why we think what we do about the natural world.

Acknowledgements: Wanderers was developed by B. Cannon Ivers, Devin Dobrowolski, and Mary Catherine Miller at Harvard Graduate School of Design, as part of the Master in Landscape Architecture program.