Drawing Creepy Places

DRAWING CREEPY PLACES //

Representing Liminal Ritual Spaces in Kuruman, South Africa

By Sechaba Maape

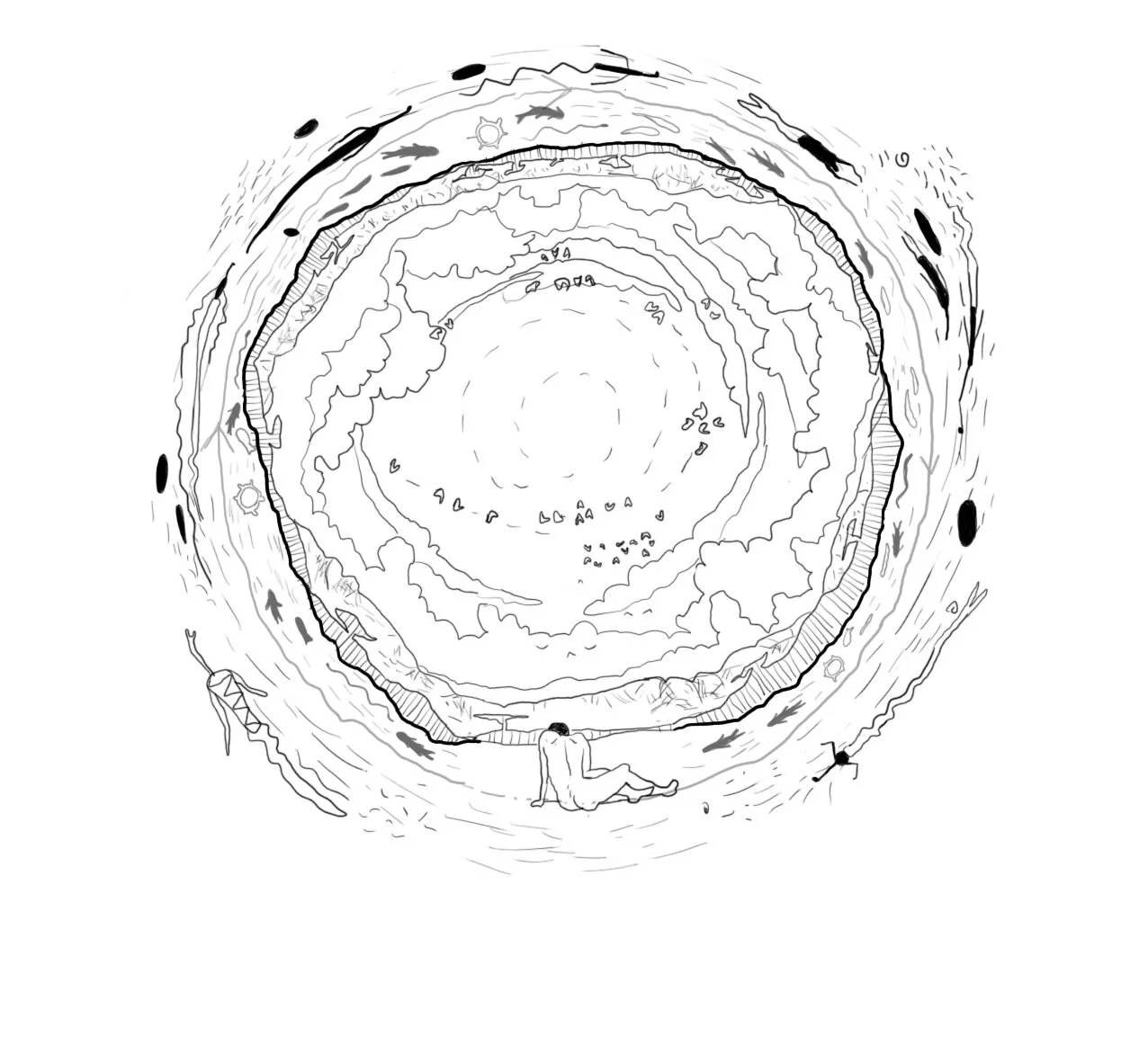

Cosmological worldview of Kuruman. Drawing by Sechaba Maape.

Kuruman is my home, and my people have inhabited its landscape for thousands of years. Its beautiful, large, and wild landscapes have always held meaning for us, and continue to do so even today. It is characterized by the great, flat Bushveld savanna, gentle hills, and a towering, crisp blue sky. It is a magical landscape, sometimes harsh with heat, and in the wet seasons, precious water collects in pans and water holes and falls down the ridges of rock shelters and caves. In the animistic worldview of some of my people in Kuruman, water, earth, sky, rock shelters, and caves are full of vitality, animated by the flux that defines the landscape. My people have always found ways to connect to this vitality through engaging particular spaces in the landscape. It is a way to be sensitive to its changes—to adapt and make meaning.

From a very young age people in Kuruman are told stories about a mythical snake. It is known to be the cause of natural forces like whirlwinds, responsible for environmental calamities, lost people, and other tragic situations. In my own life I was told about the snake primarily because of its tendency to abduct people with particular bodily features. I was told that the snake takes people with connected eyebrows, which I happen to have. Some of my earliest memories are of being told that the snake was going to take me because of the shape of my eyebrows. It turns out that this is in fact an ancient tradition connected to female initiation. The snake is known to be attracted to people with interlocking eyebrows and beauty spots because it shares these features. It is strange in form and character, travels along underwater rivers and channels, is known to shapeshift, and tricks its victims. It is especially associated with “taking” people to specific places, especially water bodies and caves.

One story is that of a young girl herding sheep who is suddenly overcome by thirst. She is drawn to a nearby waterhole, and as she draws closer, she hears the voice of a child. She goes closer still and sees that there is a small child’s hand reaching out from under the water, but the water is dark, and the rest of the body is not visible. When the girl reaches to help the child, the hand, which she now realizes belongs to the terrible snake, pulls her down into the water. Being taken, unlike willingly giving yourself up, involves the relinquishment of personal agency. I was warned that the snake would take me because my eyebrows were interlinked, something over which I have no control. Similarly, the girl had no control over her thirst; the snake stole her agency. Change is forced on those who meet and are abducted by the snake, becoming a kind of grace, invoked through ritual as, ultimately, a death of the self.

Study of mythical snake 1,2,3. Drawings by Sechaba Maape.

In my youth, though less so today, we were forbidden to go to particular parts of the landscape because these are the places where the snake resides, dangerous for people like me, with my snake-like features.(1) Caves and water bodies in general, and specific caves known to be the dwelling place of the snake in particular, are seen by some in the community as frightening. People sometimes avoid crossing a stream or entering a particular space associated with the snake.

However, these spaces, as much as they are dreaded, are precisely where teenage initiation and other ritual practices are performed. Logobate Cave, located on the fringe of Logobate village just north of Kuruman town, is a site for teenage female initiation and other forms of supplication. The Ga-Mohana rock shelters, located on a remote hill away from the nearest settlement, have also been associated with initiation rituals, but for boys rather than girls, and much less so now than in the past. Yet I was still told about Go-Mohana in my formative years, and as far back as I can remember it was where the snake resided. In both places, initiates would have to cross mythical boundaries associated with the snake, facing a lifelong and well-established fear as part of their ritual process.

These sites also have archaeological significance and are central to on-going studies of early human history. Recently Ga-Mohana has become a research site. Palaeolithic findings at both the small and large shelters such as middle stone age lithic tools may change the dominant discourse on human development in Southern Africa, which privileges a coastal hypothesis of human development rather than an inland one.(2) As the archaeological work at Ga-Mohana becomes more extensive and well known, it has raised concerns regarding the manner in which the two forms of value of the space, namely the ritual and research value, will co-exist.

By far the greatest example in Kuruman of the tension between these two ideas of the value of these ritual places is the Wonderwerk Cave. Located about forty kilometres away from the town, the Wonderwerk Cave has been extensively researched due to its archaeological value and, unlike Logobate and Ga-Mohana, is not as connected to contemporary ritual practice. Although there has been some acknowledgement of its cultural value, very little has been explored in this regard. It is a deep cave, receding about 140 metres horizontally into a hill near a water-filled sinkhole. At the back, it is extremely dark and quiet, with rock paintings on the walls—highly enigmatic images, some of known creatures and others of abstract shapes, all layered, in some places fading and vague. Both the cave and the sinkhole are known to be places where the snake resides.(3) In one story about this cave, the snake takes its victims and transports them to Chicago. There, it engages them in endless sinning, then brings them back to die and spend eternity in hell.(4)

Exploration of phenomenology of place and ritual. Drawing by Sechaba Maape

The Wonderwerk Cave was 3D scanned in 2009. Discussing their project in the Journal of Archaeological Science, the researchers involved described scanning the “most important components of the site” as an “integral part of the ongoing research.”(5) They did not, however, show an appreciation of the ritual value of the cave. They did not include local ritual practitioners or follow particular cultural protocols in their methodology, nor did they account for these protocols in their subsequent representation. The scans expose the entire cave and represent it as an empty space, presenting no evidence of the snake. The location and structure of the cave are not concealed, which may undermine its potency as a mysterious and frightening space for those who depend on that fear as part of their ritual process. The scans illuminate the darkness in which the snake resides.

This article has been excerpted for online. It was published in Healed Outcomes. Get your copy here, to read the full article and see all of Sechaba Maape’s drawings.

Cosmological worldview of Kuruman and the ritual posture. Drawing by Sechaba Maape

Notes

1. Ansie Hoff, “The Water Snake of the KhoeKhoen and /Xam” South Afrcican Archaeological Society 52, no.165 ( June 1997): 21–37, https://www.jstor.org/ stable/pdf/3888973.pdf?seq=1.

2. Jayne Wilkins et al, “Fabric Analysis and Chronology at Ga-Mohana Hill North Rockshelter, Southern Kalahari Basin: Evidence for In Situ, Stratified Middle and Later Stone Age Deposits,” Journal of Paleo Archaeology (March 2020), https:// doi.org/10.1007/s41982-020-00050-9.

3. Michael Chazan and Liora Horwitz, “Milestones in the development of symbolic behaviour: a case study from Wonderwerk Cave, South Africa,” Debates in World Archaeology 41, no.4 (December 2009): 521–539, https://www.tandfonline.com/ doi/abs/10.1080/00438240903374506.

4. Michael Chazan, personal conversation, December 2017.

5. Heinz Ruther et al, “Laser scanning for conservation and research of African cultural heritage sites: the case study of Wonderwerk Cave, South Africa,” Journal of Archaeological Science 36 (September 2009): 1848.

Bio

Sechaba Maape is an architect and senior lecturer at the Wits School of Architecture and Planning. After completing his Masters in Architecture (Professional) he went on to undertake a PhD in architecture. His thesis explored people/place relationships, ritual, and climate change adaptation among pre-historic Indigenous communities in Kuruman in the Northern Cape Province. His current work seeks to understand modern ritual spaces in South Africa, deepening our understanding of the role of these practices and places in modern society.